Editor’s note: Property tax is promised to be a hot topic before the state Legislature this year. Republican lawmakers put forth property tax relief proposals in advance of the Jan. 3 start of the legislative session. This story cuts through confusing property tax terminology to help taxpayers understand property tax, how it’s calculated and where it goes. This story originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of the Union Farmer.

As the amount of money North Dakotans pay in property tax increases, knowing how it’s calculated and where the money goes is crucial to addressing any solutions.

But property tax terminology can be confusing: mill levy, true and full value, assessed value, taxable value, effective tax rate. What are all these terms used for?

Linda Svihovec, research analyst for the North Dakota Association of Counties (NDACO), said the terms have different meanings, but taxpayers should understand the basics.

“It often sounds really complicated, but when you look at the calculations, it makes more sense,” she said.

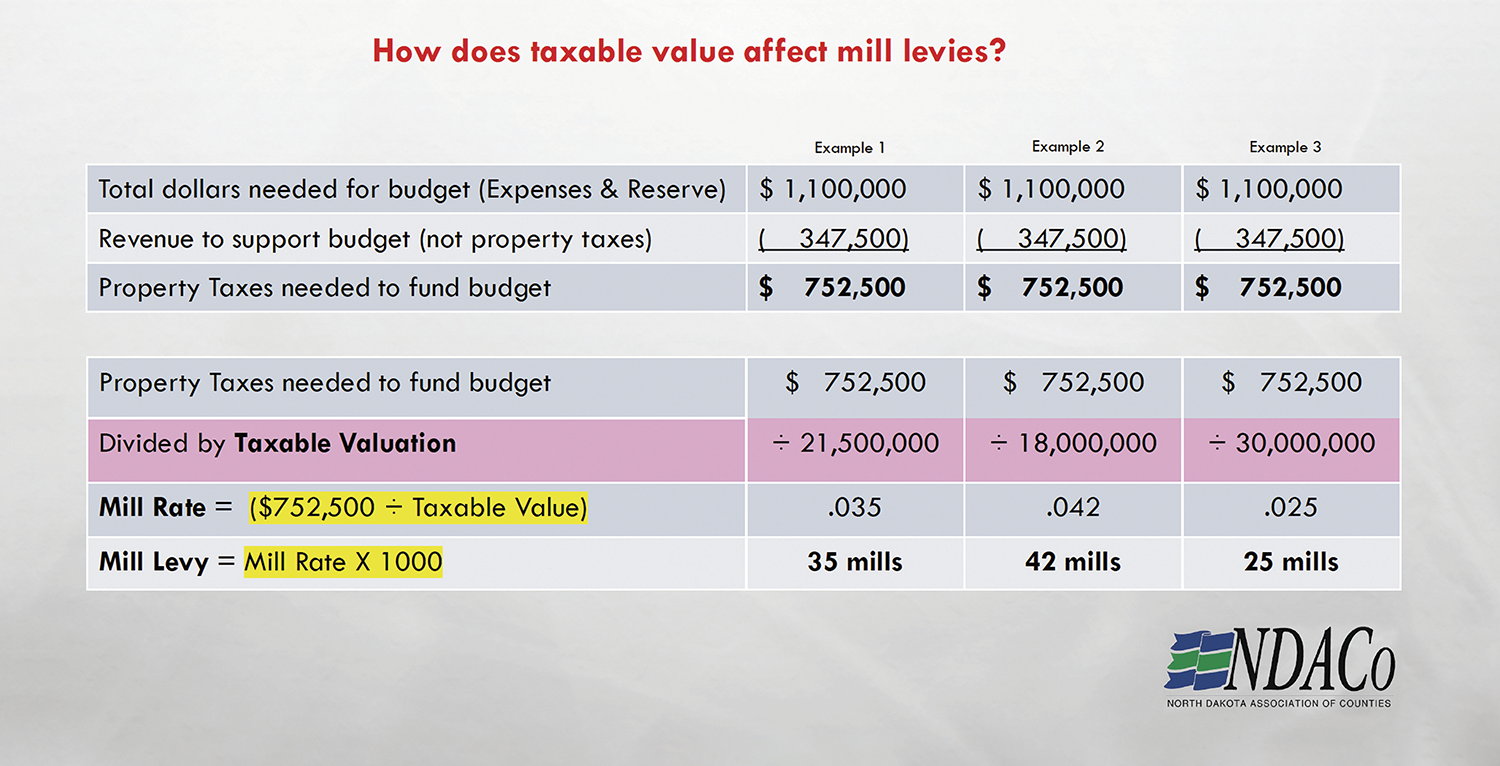

A mill is defined as 1/1000th of $1 and a mill levy is the tax rate applied to the taxable valuation of a property. A political subdivision, such as a county, calculates the amount of money needed to fill its funding gaps with property taxes by dividing that amount by the taxable valuations of the entire county. The result is the necessary mill levy.

But what is taxable value? Svihovec said the state first needs to determine what category fits the property. The state recognizes three types: locally assessed, centrally assessed and a third category typically used for electric and telephone cooperatives (referred to as “taxes paid in lieu of property taxes”).

Locally assessed values are residential, commercial and agricultural property, while centrally assessed applies to entities like railroads, pipelines, airlines and investor-owned public utilities. Centrally assessed values are overseen by the N.D. State Board of Equalization and certified by the state tax department.

To start the actual calculation, a true and full value of a property is determined by the county assessor. Svihovec said this is often different than market value, which fluctuates with the real estate market and what a property would sell for on the open market.

“The true and full value is strictly for the county or subdivision,” she said. “If true and full is done correctly, then it’s an equalized value, which means all the same things were taken into consideration from one property to the next. Market value is what a realtor believes you can get for the property.”

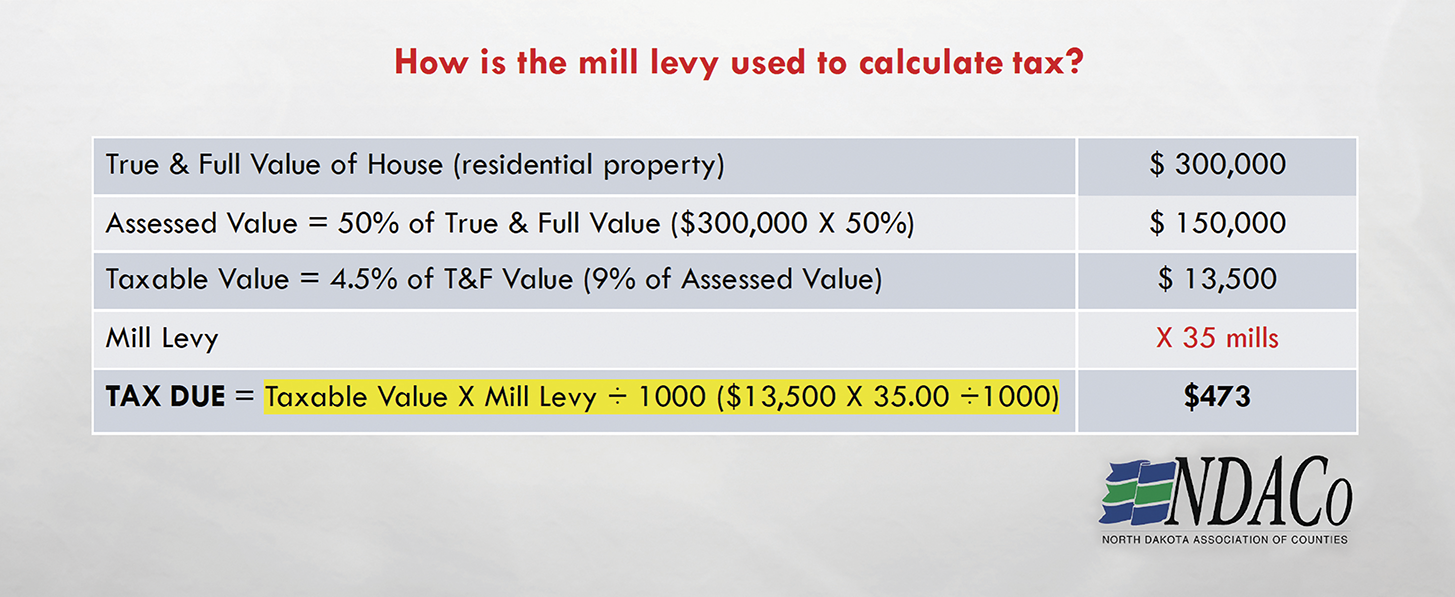

Svihovec said assessed value is also used, but that’s simply 50% of the true and full value.

But to determine property taxes, taxable value still needs to be calculated. For residential properties, taxable value is 4.5% of the true and full value. For commercial, agriculture and centrally assessed property, it’s 5%.

“If we’re talking about a house with a true and full value of $300,000, you’ll take 4.5% of that, so (it’s taxable value is) $13,500,” Svihovec said.

In 2021, Bismarck had a mill levy of 254.14. Using the previous example, a Bismarck resident for tax year 2021 would multiply $13,500 (taxable value) by 254.14 (mill levy), divide by 1000 (one mill is 1/1000th) and pay the resulting property tax of $3,430.89.

Also at the bottom of each property tax statement is a net effective tax rate, which is calculated by dividing the amount a resident pays in property taxes by the true and full value of the property (in the example: $3,430.89 divided by $300,000).

Svihovec said net effective tax rate is important because it allows for a more accurate comparison to other counties or cities, as opposed to mill rates.

WHERE THE MONEY GOES

Continuing with the Bismarck example, residents’ property taxes go to eight different entities, though four make up the bulk of the funds. Burleigh County, the city of Bismarck, the Bismarck Park District and the Bismarck Public School system use over 98% of the dollars.

The Soil Conservation District, Garrison Diversion, Water Resource District and the state make up the other roughly 2%.

In determining the mill levy and whether property taxes will increase, the subdivisions follow a strict timeline, Svihovec said.

For counties, a budget worksheet is distributed to county departments in May or early June to start the process of what the next budget cycle will need for funding. The worksheet is returned to the auditor in July, where it’s gathered for review by the county commission and the department heads. In early August, the commission approves the preliminary budget and sets the public meeting’s time and place (between Sept. 7 and Oct. 7). The budget must be filed with the auditor by Aug. 10, so estimated tax statements can be sent to the public by the end of the month. After the public meeting, the county gets until Oct. 10 to amend the final budget.

RISING PROPERTY TAXES

While income taxes have significantly decreased in the state over the last 15 years due mostly to legislative efforts, property taxes have increased considerably.

In the upcoming legislative session, Sen. Don Schaible of Mott and Rep. Mike Nathe of Bismarck said they intend to propose a bill that would provide property tax relief by utilizing earnings from the Legacy Fund, which receives 30% of the state’s oil and gas tax revenue. The fund totals nearly $8 billion.

The proposal would increase the percentage the state already pays for K-12 funding from 70% to 85%, cutting the K-12 funding burden on local taxpayers in half.

“It’s wonderful the state can look at tax relief in the amounts we’re talking about,” Schaible said. “The vast majority of comments I’ve heard have been about (providing) property tax relief.”

Svihovec said the NDACO supports property tax relief in general, but will wait until the actual bill is proposed to decide if it will support or oppose. The proposal does have a provision Svihovec said the counties don’t support – a cap that would limit what school districts can levy for the cost of education.

“Our position will definitely be as it has always been,” she said. “If they attempt to cap through legislation, either mill levies or values, we will oppose that. We will always believe that those decisions are best made locally.”

“(The public) may not completely understand how their property taxes are calculated, but they certainly understand the services they’re getting for the money. They want their garbage picked up, their roads plowed, and they want to know there’s enough law enforcement to protect our neighborhoods,” she said.

Schaible said he understands that reasoning, but has concerns about how communities are not addressing the growing problem of high property tax bills.

“I’m not a cap kind of guy – I believe that government dollars are best spent at home,” he said. “But with the complaints we’re getting and the mismanagement of taxing authority, they leave us very little room.”

Svihovec and Schaible both agreed subdivisions need to talk about increases in terms of dollars instead of mills at public meetings. Svihovec added that part of the issue is participation.

“Call out what the dollars are,” Svihovec said. “The estimated notice does do that already, but most cities and counties have little or nobody at their budget hearings and very few at their school board meetings.”

Schaible and Nathe’s proposal would require political subdivisions to “assess by dollars and not mills when planning and setting budgets.”

“We hope that it will get more people involved with the budget process and provide clarity to the public,” Schaible said.

Chris Aarhus is editor of the Union Farmer, the flagship publication of North Dakota Farmers Union (NDFU) in Jamestown. He was raised on a family farm north of Sherwood and worked for daily newspapers for a decade before joining NDFU.

WHERE ELECTRIC COOPERATIVES STAND

Don’t let the term “in lieu of property taxes” fool you. North Dakota electric cooperatives pay property tax.

The state of North Dakota recognizes three types of property tax: locally assessed, centrally assessed and taxes paid in lieu of property tax.

Investor-owned utilities (IOUs) pay centrally assessed property taxes, while electric cooperatives make in lieu of property tax payments based on their megawatt-hour sales and miles of transmission line.

“The retail electric industry is the only industry in our state that taxes the property of similar industry players on a differential basis,” said Zac Smith, communications and government relations director for the North Dakota Association of Rural Electric Cooperatives (NDAREC). “The state should provide the same tax relief to rural electric cooperatives as it’s done for the IOUs in North Dakota.”

Sen. Don Schaible’s property tax relief proposal, which will be considered during the 2023 legislative session, includes electric cooperatives, so they receive an equivalent amount of property tax relief as IOUs.

“When the Legislature makes property tax relief a priority, NDAREC supports inclusion of provisions that provide parity across the industry, and we applaud the proposal sponsors for their work to address this issue,” Smith said.