Helping Veterans, Understanding Their Sacrifice

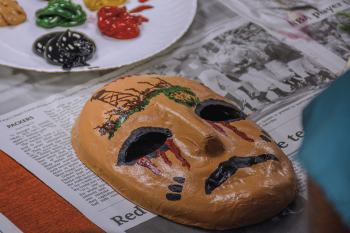

Local veterans create masks as part of an art therapy program at the Fargo VA that encourages the use of art to work through trauma. The meaning behind each mask is unique to the veteran artist, as masks are designed to depict personal experiences of trauma and recovery.

This year, images from Afghanistan entered American homes, as the United States exited the country and ended a 20-year war. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and subsequent Taliban takeover of the country was highly covered news across all media.

But for more than 4 million American veterans or active-duty personnel who have served since 9/11, those images go deeper. They trigger complex emotions and questions. Did my service matter? Were our losses for nothing?

Dr. Margo Norton, a clinical psychologist at the Fargo Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System in Fargo, has worked with Afghanistan, Iraq, Vietnam and other combat veterans who ask those questions. She provides treatment in numerous settings and helps connect veterans to the wide range of VA mental health services and therapy.

Mental health conditions are the third most frequently diagnosed category of conditions at the VA, according to the 2018 book, “Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services.” While “there’s many different doorways” veterans use to access VA mental health services, Norton says family often provides the first supportive nudge.

“It’s usually family members saying, ‘We’re really worried about you.’ It’s not (the veteran) independently saying, ‘I need help.’” Norton says. “There’s this idea that time will heal, that things will fall back into place and ‘I’ll get over it.’ We never know when we’re not going to be able to get through it without some help.”

MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

Courtesy photo

Norton’s first exposure to veterans in her field was working in a post-deployment clinic for the VA. The clinic served combat veterans returning from warzones in the Middle East and was often the first touchpoint to the VA system.

“A lot of times, when (veterans) first come home, they’re not ready or not interested in doing intensive mental health care, because they’re excited to be back home and with their families and get on with their life,” she says. “We really try to give them at least information and encourage and get them engaged in the VA in some way as soon as possible, so they know when they’re ready to come back to us … that we’re there for them when they might need it.”

While the need for mental health services and access points are unique to each individual, veterans may seek treatment for depression, anxiety, psychological distress, drug or alcohol dependence, traumatic brain injury (TBI) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Also common among combat veterans is treatment for moral injury, which Norton describes as the “guilt and shame part of trauma and PTSD.” Moral injury in the context of war comes from participation in actions related to combat warfare, such as killing or harming others, or indirectly from acts like witnessing a death or others dying, failing to prevent similar immoral acts, and granting or receiving orders that can be viewed as immoral or inhuman.

When a veteran first accesses mental health services through the VA, an initial intake evaluation is done. Information is gathered about the patient’s relevant history, background, military service and current issues. Then, a mental health provider performs a diagnostic assessment. Together, the patient and provider review the evaluation and discuss possible treatment courses. Treatment options are diverse and range from individual, group, familial, inpatient, outpatient or telehealth settings to evidence-based psychotherapies, written-exposure therapy and even art therapy.

The most important part of the process, Norton says, is involving the veteran in the decision.

“We call them shared decision-making sessions, because we want the veteran very involved in the decision,” she says. “We’re not just prescribing. We want patients to have some personal choice. We lay out the options and ask, ‘What do you think is going to work best for you?’”

THE STIGMA

Interestingly among the veteran population, Norton hasn’t observed the stigma associated with mental illness that has been observed more broadly in society.

“I think in some ways, it’s almost more acceptable to have a mental health issue as a veteran. It’s almost the opposite (of being stigmatized); it’s almost more assumed. But at the same time, poorly understood,” she says.

Regardless of the perception of mental illness, Norton offers advice for family members or friends in how to approach a conversation with their veteran about getting help.

“Don’t pressure. Don’t push. Don’t insist,” she says. “Everyone has a different idea or way of wanting to be approached. Make sure they know that the door is always open for discussion.”

If the concern is suicide, ask them about it, Norton says.

“Asking someone about suicide or if they are suicidal is not going to trigger someone to make an attempt on their life,” she says.

PHOTOS COURTESY ROSS TWETEN/FARGO VA HEALTH CARE SYSTEM

In 2019, the U.S. veteran suicide rate was 31.6 per 100,000, substantially higher than the 16.8 suicide rate among the U.S. non-veteran population. Of all suicides in North Dakota in 2019, 11.2% were veterans.

Information from the 2021 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report suggests VA mental health care has the potential to improve these statistics. Among the average 17.2 veteran suicides per day in 2019, an estimated 10.4 had no encounters with the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) compared to 6.8 who had encounters with VHA, the report says.

Commit the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline to memory: 1-800-273-TALK or 1-800-273-8255. The lifeline provides free, confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources, and best practices for professionals.

ANOTHER HEAVY ROCK TO CARRY

Dr. Joseph Geraci, a clinical psychologist at the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in the Bronx, N.Y., deployed four times to Afghanistan before retiring in 2018 as an Army infantry lieutenant colonel. In an interview with the “VA Research Currents,” Geraci says the recent events in Afghanistan can be viewed as a form of moral injury and have the potential to leave veterans more susceptible to psychological challenges.

“Processing emotions related to the Afghanistan withdrawal may be a sizeable burden for some veterans that can weigh them down,” he says. “It is yet another heavy rock for them to carry in their ‘rucksacks.’ At this point, it’s just anecdotal, but I am concerned that the situation in Afghanistan is going to increase the suicide risk for some post-9/11 veterans.”

Geraci went on to offer insight into the emotions he and other post-9/11 veterans may feel from recent events in Afghanistan: anger, sadness and fear.

“We gave so much for our nation’s mission in Afghanistan, including our blood, sweat and tears,” he says. “Looking at the legacy of some of the units that I deployed with to Afghanistan, we accomplished so much: building schools and roads, bolstering Afghan governance and reducing threats from the Taliban and other insurgents. … And then, almost in the blink of an eye, it’s like our 20 years of service, sacrifices and accomplishments were wiped away.”

The fear, Geraci explains, is for the Afghan partners they stood next to in battle and the retaliation by the Taliban they now face.

Norton says many of the Afghanistan veterans she works with have expressed similar emotions and even frustration with the dialogue surrounding the recent events in Afghanistan.

“I do hear veterans say a lot, particularly with the Afghanistan withdrawal, is that it’s really hard to take when people who were not in the military share their opinions,” she says. “It’s like, ‘Who is that person to have an opinion?’ People who’ve been there, who’ve fought there, have a right to an opinion. Be really careful about sharing your opinions and criticizing whoever or whatever.”

UNDERSTANDING THE SACRIFICE

As someone who is surrounded by veterans every day at her job and at home (her husband is a veteran), Norton’s work goes beyond therapy. She is an advocate for veterans. She has heard their stories. And she is part of a team at the VA whose collective goal is to make our communities more veteran-friendly and more compassionate to the challenges of veterans.

As we recognize Veterans Day this month, how can we be better neighbors?

“Be open to learning more about the sacrifice (veterans make), not just ‘thank you for your service,’ but really having a more intimate understanding,” Norton says.

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.

To enroll in VA health care, visit www.va.gov(link is external) or call the Fargo VA Health Care System at 701-239-3700.

VETERAN ART EXHIBIT PROMOTES HEALING AND RECOVERY

Trauma experts have explored the role creative arts can play in the healing and recovery process of veterans and military service members, particularly those suffering from post-traumatic stress or traumatic brain injury. “Warriors in the North: Healing Through Art” highlights this creative work in the Red River Valley with an art exhibition produced by local veterans and directed by the Fargo VA Health Care System and the Historical and Cultural Society of Clay County.

The exhibition is currently on display at the Hjemkomst Center in Moorhead, Minn., through March 6, 2022. It includes portraits by veteran photographer, Dr. Ken Andersen, paintings by a local combat veteran, masks designed to depict personal experiences of trauma and recovery, and music and writing projects created to process and share traumatic experiences. Workshops and collaborations were facilitated by Dr. Margo Norton, Wendell Affield, Amy Tichy and Dan Hudson.

A special Veterans’ Performance Showcase featuring writing and music projects from the “Warriors in the North” exhibit will be held from 6-8 p.m Wednesday, Nov. 10. This is a free public event, but does require an advance ticket, with limited space available. The event will also be livestreamed online via Zoom and Facebook. Visit www.hcscconline.org/warriors(link is external) for ticketing, webcast or exhibit information.

Warriors in the North: Healing Through Art

▶ On display through March 6, 2022

▶ Hjemkomst Center | Moorhead, Minn.

▶ http://www.hcscconline.org/warriors