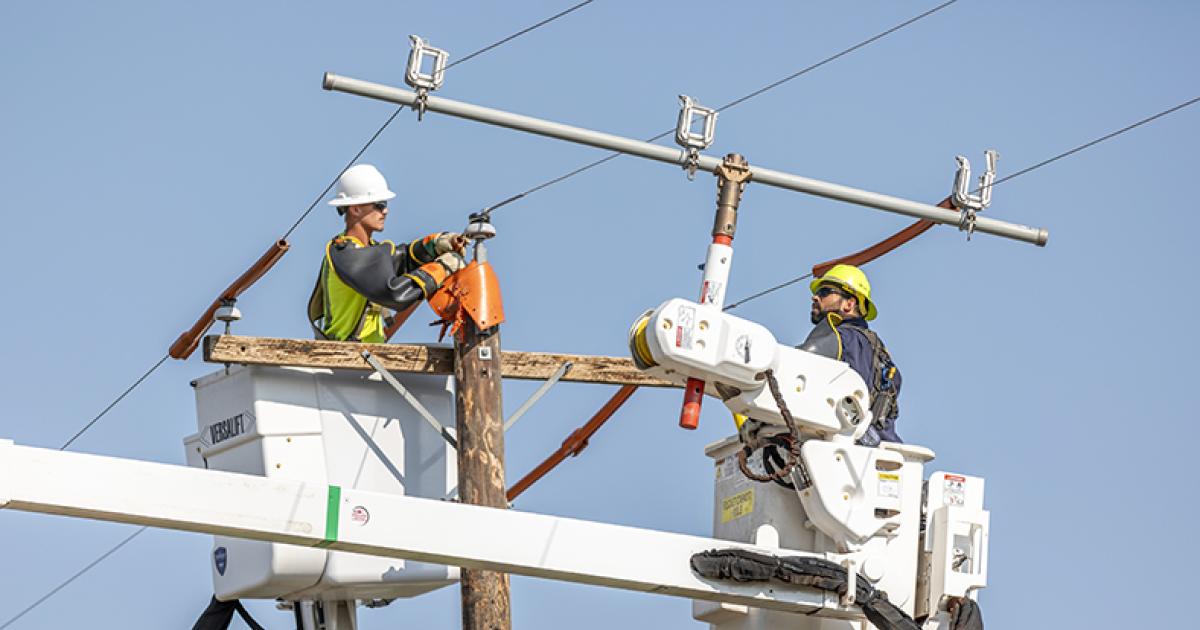

NDAREC Photo

When a severe storm sweeps through North Dakota, toppling power poles and triggering outages, electric cooperative members may ask: “Why doesn’t my local electric cooperative bury the lines underground to protect them from the elements?”

The answer isn’t simple.

Electricity is delivered to a home, farm or business through a complex system that includes power generation, transmission and distribution. Your local electric cooperative is a distribution cooperative that owns and maintains a mix of overhead and underground power lines. Each of North Dakota’s electric cooperatives weighs the advantages and disadvantages unique to that system when deciding if line should be strung through the air across poles or buried underground.

Plagued by Mother Nature’s icy grip routinely pulling down poles, Dakota Valley Electric Cooperative (DVEC) in central North Dakota hasn’t built any new overhead line in years, opting instead to bury new lines.

“In this part of the state, overhead is just tough,” says DVEC General Manager Mark Kinzler, pointing to three major storms in the past six years. “We virtually build no overhead at all anymore.”

In the midst of the busy Bakken, Mountrail-Williams Electric Cooperative (MWEC) notes avoiding a maze of underground pipeline is just one factor when considering burying power lines.

“Cost and reliability are probably the two major components we’re going to look at,” says MWEC Senior Electrical Engineer Scott Iverson. “We’re trying to strategically pick what we put underground.”

In-between, North Central Electric Cooperative (NCEC) continues to install underground where it makes sense.

“It has to be strategic to keep expenses in line,” NCEC General Manager Jon Beyer says.

Although underground lines may seem attractive during storms, since the lines are not exposed to extreme weather, co-ops carefully balance reliability and affordability to best serve their members.

As of 2023, North Dakota’s electric cooperatives had 39,636 miles of distribution lines overhead versus 25,271 miles or 38.93% underground. Comparatively, the ratio in 2015 was 43,728 miles of distribution line overhead and 20,941 miles or 32.38% underground.

Affordability

About 10 years ago, installing underground cable cost two or three times more than the initial installation of overhead line. That gap has closed, but underground is still more expensive.

“It is a little more expensive and it’s tough for us to justify taking a line out that’s perfectly good and just burying it. A line that’s been there for 50 years, that’s still straight as an arrow and working just fine as far as the capacity and strength, it’s tough to make that financial decision to put that underground, unless there is a real reason to do it. So, that’s why we still continue to have a lot of overhead line and we probably will continue to into the future. It’s just not feasible to bury everything,” Beyer says.

“Cost can be higher in some situations, because we often install larger conductors due to the nature of the oil field,” Iverson says. “The larger the conductor, the larger the difference in cost. There are fewer equipment operators who have the equipment to handle that size of cable and weight.”

When a storm strikes

Seeing miles of power lines pummeled to the ground by ice or wind can be gut-wrenching for an electric cooperative.

“Even a heavy frost event can cause you some grief with overhead,” Kinzler says.

Serving a part of the state where ice and frost reign, DVEC now has about 41% of its line underground, burying both new and old line.

DVEC studies its outage statistics, particularly where frost is an issue, and tests 10% of its poles each year. Where a line is starting to fail, the co-op then considers placing it underground.

“If we have a stretch of poles that are bad, we prioritize that for underground,” Kinzler says. “A lot of it is outage statistics. If areas are more susceptible to ice or if the line condition is not good, we prioritize those.”

“Over the last 10 years, our outage statistics have gotten considerably better with our triaging the problem areas,” Kinzler says. “For us, from an outage perspective, once you plow in underground, you don’t have near the problems.”

Members may wonder why underground line isn’t installed while storm damage is being repaired. Federal disaster assistance and reimbursement regulations don't allow the cooperative to make improvements to a line when it is repaired, beyond what existed before the storm damage. Replacing a damaged overhead line with underground line, for example, would be considered an upgrade by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and thus not eligible for FEMA dollars. Additionally, during outages, the focus is on restoring power, rather than replacing line. And the process to install underground takes months.

“If we have an ice storm in April, we need to put the power back on. We don’t really have the option of just burying it underground. One, the ground is typically going to be frozen, so we can’t put in underground. Two, there are some environmental concerns,” Beyer says. Cooperatives must comply with federal regulations regarding environmental concerns, historical artifacts and other guidelines before burying line, which may take months.

“Every year, our construction plan includes transition of overhead to underground lines. However, the April 2022 storm, which cost just over $21 million dollars, emphasized the need to install more underground lines moving forward. Over time, these solutions will help create the most robust system possible and continue to cut down on outage time and frequency, especially when it comes to storm response,” Iverson says.

Overhead line is not only susceptible to weather, but it is also prone to farming equipment accidents.

DVEC experiences 30 to 40 equipment strikes a year of either poles or cabinets.

“We have poles that get knocked over every year by people farming around them,” Beyer says.

Reliability

Similar to other technology, underground cable has evolved over the years. Underground cable in the 1970s and 1980s did not have a jacket and faults were common.

“Everyone agrees among co-ops and other utilities that particular vintage was horrible,” Iverson says. “The 1980s vintage line almost ruined underground. ... It would take an entire day to find a fault.”

Poles from the 1940s and 1950s, however, are still standing.

With nearly 30% of its line underground, NCEC still has original poles standing.

“You can tell what year a co-op was founded based on the oldest poles on their system,” Iverson says. Those poles, some of which are still standing, were treated with a large amount of creosote. Newer poles have a shorter lifespan due to different treatments.

“Those days of a pole lasting 75 years are gone,” Iverson says. As the pole’s lifespan decreases and the underground line’s lifespan increases, both will now last an expected 35 to 40 years, he says.

And with improved reliability, underground cable is now more often considered.

“We have a policy if a piece of line faults a number of times, we’ll just replace it, because we know it’s a reliability issue,” Beyer says. “As we move forward, we do more and more underground all the time. For us in North Central, in particular, we try to have all of our main feeders tying substations together as underground, then they’re less prone to weather, disruptions, ice and those kind of things. But we do have a lot of overhead tapping off of that underground and that's the mix for us. Going forward, we do have more underground going in.”

When MWEC was building new line to serve the Bakken, it was quickly building overhead.

“There were a couple of factors. One was the speed of construction at that time. The other reason was with all of the energy activity, there was also a lot of pipeline activity, increasing the chance of hitting underground lines. So, to avoid those types of outages and those risks, the installation of overhead lines was a better option at that time,” Iverson says.

At MWEC, road crossings have also become a priority for underground line. In 2023 alone, MWEC invested nearly $7 million to bury main tie lines, and nearly $2 million to bury overhead road crossings.

“We have so many high load moves hauling large tanks down our roads that we have constant interruptions to our work flow,” Iverson says.

NCEC has other factors to consider.

“Underground is nice, because you don’t have to worry about the tree trimming,” Beyer says. The cooperative also bores under deep water with underground line.

“Boring has changed underground quite a bit, because we’re able to go under places, around things, through things a lot more. So, road crossings are really nice. We don’t have to worry about anything hitting our lines or the lines falling, becoming low with frost or anything over a road right of way. So, there's definitely benefits for underground on any type of road crossing,” Beyer says.

Underground, however, might not be the best solution in fields using drain tile or in rocky areas.

And it cannot be retrieved.

“Once it’s in the ground, it’s there forever,” Beyer says, while an abandoned overhead line can be removed and reused.

Finding faults

While underground line doesn’t topple during severe weather, it is not without faults and power outages.

Detecting and repairing faults in underground power lines is more challenging compared to overhead lines, where a visual inspection will find a fault.

“It can be a little tougher sometimes, fixing it, and may take a little bit more time,” Beyer says.

A traditional method to find an underground fault involves a thumper, which puts a voltage/current on the line as crews listen for a thump at the fault. Utilizing this method, a fault on an underground line will take two to three times as long as an overhead fault, Iverson says.

Newer software now allows co-ops to isolate, detect and repair faults faster. Fault location, isolation and service restoration – or a self-healing grid – utilize smart devices to find a fault and reconfigure the system through the software. It allows cooperatives to redirect the flow of electricity, safely repair the section of line that is out and restore electricity, in less time. This technology works on both underground and overhead, Iverson describes.

“Whether we are hardening overhead lines, beefing up poles carrying heavy equipment or relocating overhead to underground lines, the needs of our members is always the priority,” Iverson says. “Our goal is to provide affordable and reliable power to our members.”

___

Luann Dart is a freelance writer and editor who lives in the Elgin area.