With young families leaving LaMoure due to the inability to find child care, a group of local residents met in July 2019 to start developing what is now Little Loboes Bright Beginnings. The group secured $200,000 in crucial supplemental financing through a partnership with their local electric cooperative, Dakota Valley Electric Cooperative, to help construct its 4,500-square-foot child care and preschool facility. Photo Ccourtesy Little Loboes Bright Beginnings/Dakota Valley Electric Cooperative

“A child care crisis.”

That’s how Gov. Doug Burgum described the state of child care in North Dakota, speaking at a press conference in September 2022 to pitch his child care plan.

“In many cases, parents have to choose between working and paying for child care, or not working at all,” Burgum told the Legislature in his executive budget address in December. “Currently, child care costs account for 15% to 40% of the average household budget in North Dakota, which often isn’t sustainable for young working families.”

Given the data, it seems unlikely few would argue Burgum’s point. North Dakota families paid between $7,800 and $9,800 on average for child care in 2021, according to the December 2022 Kids Count North Dakota report, “North Dakota’s Child Care System: Investments Needed to Support Families and Child Care Businesses.”

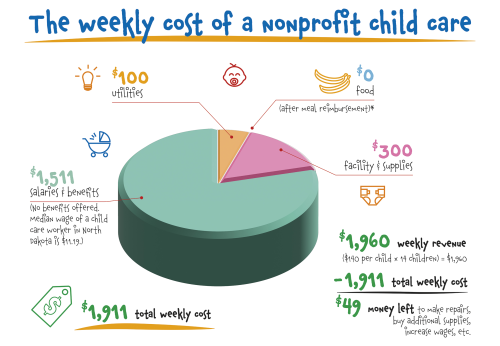

|

| *The facility still pays out-of-pocket for weekly food expenses, which are reimbursable through the federal Child and Adult Care Food Program administered by the state of North Dakota. ____________________________________________________________________ SOURCE: This example uses data provided by Linton Lions Daycare, a nonprofit child care facility in Linton, where the median household income in 2021 was $39,500. |

How did we get here?

One wouldn’t have to look far to find examples of the child care need and challenges faced by working families across North Dakota. In fact, Lori Capouch, rural development director for the N.D. Association of Rural Electric Cooperatives (NDAREC), says the child care “crisis” has been rippling through rural communities for years. Problems like having limited to no child care access, hiring and retaining workers, and the ability to cash flow a child care business have been documented by Capouch and her team for more than a decade.

Of the approximately 62,000 children under age 6 in North Dakota, more than 70% have parents in the workforce. In 2022, there were only enough child care and early education slots for 81% of these children of working parents. Certain areas of the state fall further behind in access to child care and early education: Twenty counties meet less than 60% of the demand for working families (Benson, Burke, Dunn, Eddy, Kidder, McKenzie, McLean, Mercer, Morton, Mountrail, Oliver, Renville, Rolette, Sargent, Sheridan, Sioux, Slope, Towner, Wells and Williams, according to the Kids Count report).

“We do know there are people working in one town and have children (with a child care provider) in one or two other towns, so they are driving quite a long way to get their kids taken care of,” Capouch says.

If child care is available in a community, finding child care workers and narrow operating margins make the child care business a tough sell.

“Child care businesses must balance the true cost of providing high-quality care with what parents can afford. Because of this, many child care businesses operate on narrow margins and often cannot pay employees a (competitive) wage. Employee wages and benefits make up more than half the cost for most child care businesses, with other expenses going toward rent and utilities, administrative costs and materials. Low wages for child care workers lead to staffing instability, making it challenging for child care businesses to retain workers and remain open,” the Kids Count report states. The median wage across North Dakota for a child care worker is $11.19 per hour.

Recently, Little Loboes Bright Beginnings, a nonprofit child care center in LaMoure that operates in a facility owned by the local community development corporation, and Energy Capital Cooperative Child Care, a nonprofit, cooperative child care center in Hazen, had to drop families because they didn’t have enough workers to provide for the children in their care.

And that’s a “crisis” the community of LaMoure doesn’t want to experience again.

“A group of us got together in July of 2019 to try and get a day care brought to town, because we had a lot of younger families that were looking to leave, and actually leaving LaMoure, because they couldn’t get child care,” says Sara Weber, Little Loboes Bright Beginnings.

“(Having child care access in LaMoure) has brought more families to the community, more families have stayed in the community. It’s helped with job openings that are here, and filling those spots, because there’s a place for people to take their children,” she says.

NO CHILD CARE, NO WORKFORCE

In his budget proposal before the Legislature, Burgum includes $76 million in recommendations to improve the affordability, availability and quality of child care programs in the state. The inclusion is part of the governor’s approach to addressing a statewide workforce shortage, which Burgum identifies as the No. 1 barrier to North Dakota’s economic growth.

“By investing in child care, we can make it easier for North Dakotans – especially young families just beginning their careers – to participate in the workforce, help grow our economy and support our local businesses and communities,” he said.

While Burgum has received broad support for his proposal, some advocates say more needs to be done.

“Child care is a labor issue that is unique in that it affects all other workforces. And, like other businesses, child care providers struggle to recruit and retain workers. Child care workers are essential and deserve wages that reflect the challenging work of caring for young children,” says Erin Laverdure, North Dakota Child Care Action Alliance. “A better child care system is in reach for North Dakota, and it requires a more comprehensive approach than what the governor presented.”

“If we’re really serious about workforce, how can we not be serious about child care? And if it is a crisis, we need to give it the same attention we’ve given to other crises – all hands on deck,” says Josh Kramer, NDAREC executive vice president and general manager. “Access to child care and child care workers is a need in all areas of the state, including our small towns and rural areas, so attention must also be paid to the geographic distribution of aid or support.”

Kramer leads the statewide association of North Dakota’s electric cooperatives, which have a track record of supporting child care facilities in communities they serve. Electric cooperatives have provided low-interest financing for community-owned, nonprofit and cooperative child care facilities through the Rural Development Finance Corporation (RDFC) and its $8.37 million revolving loan fund. Additionally, the Rural Electric and Telecommunications (RE&T) Development Center, led by Capouch, has provided technical assistance and business development guidance to child care groups, cooperatives and businesses. More than a dozen communities have benefitted from the investments electric cooperatives have made to build child care capacity in North Dakota.

The community of LaMoure, for example, worked with its local electric cooperative, Dakota Valley Electric Cooperative, to secure $200,000 in crucial supplemental financing from RDFC’s community capital loan fund, which was used to help construct the 4,500-square-foot Little Loboes Bright Beginnings child care and preschool facility there. The RE&T Development Center also helped lead Hazen community members through the formation of its nonprofit child care cooperative, Energy Capital Cooperative Child Care.

“We try our hardest to help the child care providers not have debt when they open up, because it won’t cash flow,” Capouch says.

NO COOKIE CUTTERS

As the Legislature considers how to address the state’s child care “crisis,” Capouch offers some insight from her decades-long experience working alongside rural communities to develop solutions to quality-of-life issues, like child care.

“Communities have personalities, and even though there’s cookie cutters you can follow, nobody does. Every community has their own way they want to develop something. There’s no cookie cutter that will fit two communities the same,” she says. “Most of our communities have less than 500 people, so the model has to be something that will support smaller numbers of children.”

While there may not be one cookie-cutter solution for the child care crisis in North Dakota, employers and the state can learn from the electric cooperative model of flexibility.

“The state has to come out with programs with definitions, and it doesn’t always have the ability to be flexible. We get stuck in formulas, as a problem of government, not just our state,” Capouch says. “That’s why, for us, as electric cooperatives, we’ve been able to help. We found things that work, like the cooperative model, private donations, foundation grants and our revolving loan fund. Those are things that work, because they’re flexible. They allow progress to happen in a manner that best suits the community within their timeline.”

“As employers and leaders, finding innovative ways to support access, quality and affordability of child care is an issue all must own and contribute time and resources,” Kramer says.

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.