A local take on the youth vaping epidemic

Kidder County High School Principal Michael Wachter leads the anti-vaping charge in his school by focusing on mentorship and recovery, not punishment. Photos by NDAREC/Liza Kessel

“Your kid has done it or seen it done, and I can almost guarantee it,” says Kidder County High School Principal Michael Wachter.

The “it” Wachter describes? Vaping.

Using an e-cigarette is commonly called vaping. E-cigarettes are battery-powered devices that heat a liquid into a vapor that can be inhaled. The vapor may contain nicotine, flavoring, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and other chemicals.

“It’s happening,” he says. “Your son or daughter has seen a device being used. And that right there is peer pressure in itself.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is warning parents, youth, health care providers and schools about the dangers of vaping in kids, teens and young adults. While nicotine is known to harm the developing adolescent brain, scientists still have a lot to learn about other vaping-related substances and the long-term effects of vaping.

According to the 2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey conducted by the CDC, about 6.2 million U.S. middle and high school students were considered current tobacco users, having used in the past 30 days. Those figures suggest that 1 in 3 high school students (4.7 million) and 1 in 8 middle school students (1.5 million) nationwide are current tobacco users.

The most popular tobacco product among students? E-cigarettes, or vaping devices – for the sixth year in a row. The CDC found that e-cigarettes are the most commonly used tobacco product among high schoolers (27.5 percent) and middle schoolers (10.5 percent). E-cigarettes outpace cigars, the next most popular tobacco product among teens, by more than three times.

Wachter, a first-year principal who taught technology and engineering in Kidder County for 12 years prior, says a local vaping awareness has been present for about three or four years. Last year, though, the vaping problem really took root.

“We caught students all the way down to the seventh-grade,” Wachter says. “That’s when everyone said, ‘Woah, this is a problem.’”

Then, at the start of the school year, a local news story came out about a Bismarck teen who nearly died from vaping, a habit she developed merely two years earlier. Tobacco companies marketed e-cigarettes as a healthy alternative to smoking cigarettes, and she believed it. The teen developed fluid in her lungs and horrible chest and back pain, which her doctors compared to the pain level of a heart attack. She has since traded in her vaping device for an inhaler.

“That really shook us,” Wachter says of the teen’s vaping experience.

Beyond the well-known dangers of smoking and tobacco use, Wachter says the unknown with vaping makes this youth epidemic even more frightening. Research on vaping is limited, and the “how” and “when” of its effects are largely unclear.

These concerns are felt in schools across North Dakota. State and national efforts are underway, through regulation, awareness and health research, to prevent the spread of this dangerous vaping epidemic, but it’s up to the boots on the ground to tackle the impacts on today.

A STEP AHEAD

Kidder County School Superintendent Rick Diegel sent a letter to parents in September regarding vaping. It detailed action steps the school district would be implementing in an effort to stomp out local youth vaping. The district also identified patterns of student behavior that could signal incidence of vaping, including frequent restroom breaks, leaving the school frequently, frequent “disappearances” when around family, agitation resulting from an inability to be alone and increased thirst, from vaping dry mouth.

“We were seeing patterns and trends – kids using the restroom at the same times, going out to their vehicles often. Some would even have their parents (unknowingly) call to give their child permission to run home for 10 minutes,” Wachter says. “The kids are almost a step ahead of everything we (at the school) do and their parents.”

The school district also brought in University of North Dakota (UND) professor Frank White, whose research agenda focuses on the vaping epidemic and e-cigarettes, for two vaping presentations – one for students and one open to parents and the general public. White’s message was honest.

“He’s not a scare-tactic guy. He basically said that although we don’t know a lot about vaping, what we do know, scares us,” Wachter recalls.

For example, White explained the dangers of vaping nanoparticles, which are particles so small they can go through a wall. These nanoparticles get so deep into one’s lungs that they can’t be coughed up. Users develop “vaper’s cough” as a result.

Twenty confirmed or probable cases of vaping-related illnesses were reported by North Dakota hospitals from 2019 through Jan. 2. Ten of those cases were individuals age 18-24 and two were under the age of 18.

After finding out that a former student, whom Wachter had a very close relationship with, had started vaping, he was devastated.

“It drilled me,” Wachter says. “I’m passionate about this because I care about the kids. I don’t care as much that it’s illegal or it’s part of my job to do this. Vaping could affect the rest of their lives, and I want the kids to believe we’re doing something about this because we actually care about them.”

Wachter’s care and concern for his students is obvious, and mentorship is big in his book. Under his leadership, Wachter has started relationship mapping with his staff this year. The goal is to foster positive student-adult relationships in school.

“We want all our students to have an adult in this school, a mentor, that they know they can go to for anything,” Wachter says. “Maybe there are issues at home, or they have a friend contemplating suicide. We want every student to have someone in this school they can approach with an issue or problem.”

DOING SOMETHING

In addition to vaping awareness and mentorship efforts, Kidder County High School, on KEM Electric Cooperative lines, has installed vaping detectors in bathrooms and developed a tobacco education and recovery course students caught vaping must complete. As an alternative to in-school or out-of-school suspension, the program is a series of 45-minute afterschool sessions held over a consecutive five-day period.

“In-school and out-of-school suspensions don’t make much sense to me,” Wachter says. “That’s why this program is after school. We’re keeping them here so we can try to do the best we can while we got them.”

The first day is a 45-minute meeting with Wachter, the student and his/her parents or guardian(s). Together, they discuss factors that created the problem. Trust-building is a natural part of the process, too.

“Once they’re caught, they’re caught,” Wachter says. “I tell them, ‘You can’t get into any more trouble than you’re in right now, so you might as well be honest, so we can get you help.’”

On the second day, students meet with the Kidder County Tobacco Coordinator to discuss techniques and resources for quitting vaping. This day is also important because the coordinator is a neutral third party, which allows the student to open up more than they might with their parents or school administration.

The third day is all about education. Students review an anti-vaping toolkit developed by Essentia Health, “Don’t Blow It: Anti-Vaping Campaign,” to learn the dangers of vaping and hear firsthand accounts from other high school students.

Students are required to complete a recovery plan document on the final two days of the program. The document asks students to answer three questions in written format. They are asked to explain what influenced their decision to experiment with vaping, what they learned about the dangers of vaping during the program and detail their plan for recovery. Wachter says that last question is the most important, because students are asked to identify mentors they can go to for help, lay out a plan for lifestyle changes and identify resources for prevention and support.

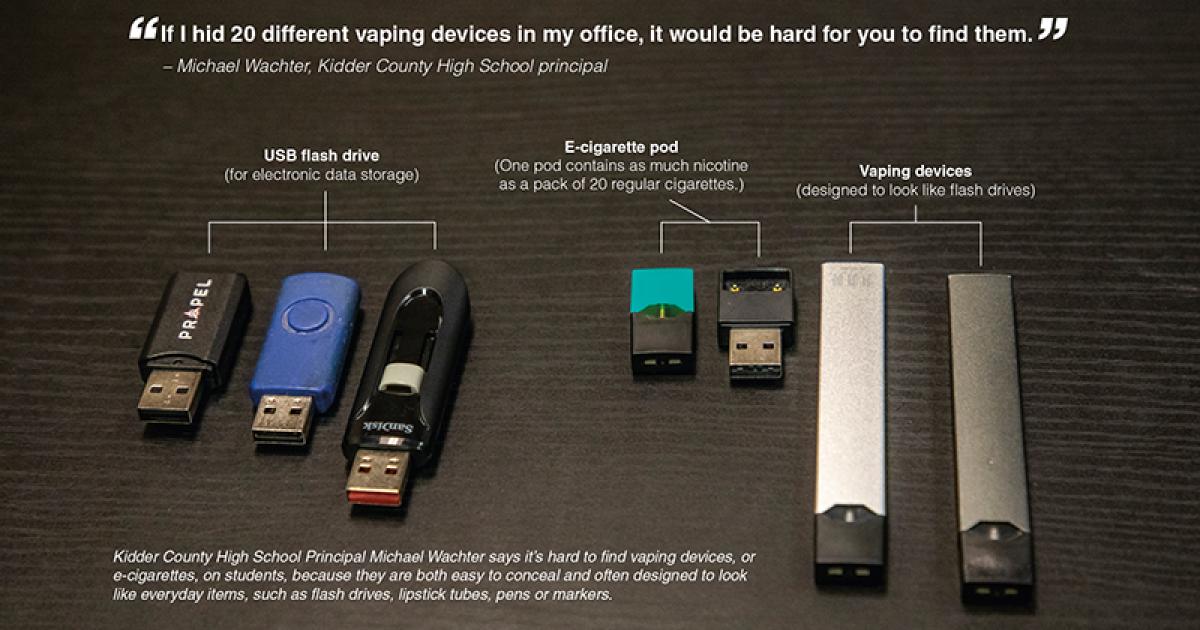

“I had it in my head that I wanted (the program) to be about recovery and not a punishment,” Wachter says. “I don’t want kids to think I’m this ninja in the hallway looking for vaping devices. I’m not angry. I’m not mad at the kids. I know that so many things about this are designed to hook the naïve kid.”

While Kidder County’s tobacco prevention program seems to be working in their school of 141 kids, Wachter recognizes the challenge larger schools have in combating vaping use.

“I think we’re at an advantage in Class B,” Wachter says. “We’re catching six students a semester. They’re dealing with six students a week.”

TURNING THE TIDE

Wachter’s message to parents? There’s no demographic to vaping.

It’s an important observation Wachter wants people to understand.

“Parents want to believe their kids aren’t doing this; that social media is safe; that their kids are doing the right thing,” Wachter says. “But anyone can really do it – your ‘red flag’ kids, your star on the basketball team, your prom queen.”

Wachter is not a self-professed expert on vaping. Like everyone else, he’s learning along the way. But he is hopeful. It appears the tide is turning, locally, at least.

“I was hoping the popularity (of vaping) would wane like the fidget spinner,” he says. “It hasn’t, but it does appear, in our school, it has taken a significant turn in the right direction.”

He credits the success of anti-vaping campaigns, new vaping regulations, and the public becoming more informed on vaping for a large part of the recent downward trend locally.

“Something we’ve done is working,” Wachter says.

For now, it seems the bootstraps are holding up in Kidder County.

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.

NEW VAPING REGULATIONS

New federal regulations aim to curb teen vaping use:

• Raising legal age – On Dec. 20, Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed a new age limit law, raising the minimum age to buy tobacco products like cigarettes, e-cigarettes and vaping products that contain nicotine from 18 to 21.

• Flavor ban – On Jan. 2, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced a ban on most flavored e-cigarette cartridges or vaping pods, including fruit and mint flavors. Tobacco and menthol flavors will still be available.

RESOURCES AVAILABLE

The N.D. Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have created numerous vaping resource materials for parents, educators, health providers and the general public. Information is regularly updated and can be accessed online by visiting:

• www.health.nd.gov/vaping(link is external)

• www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes