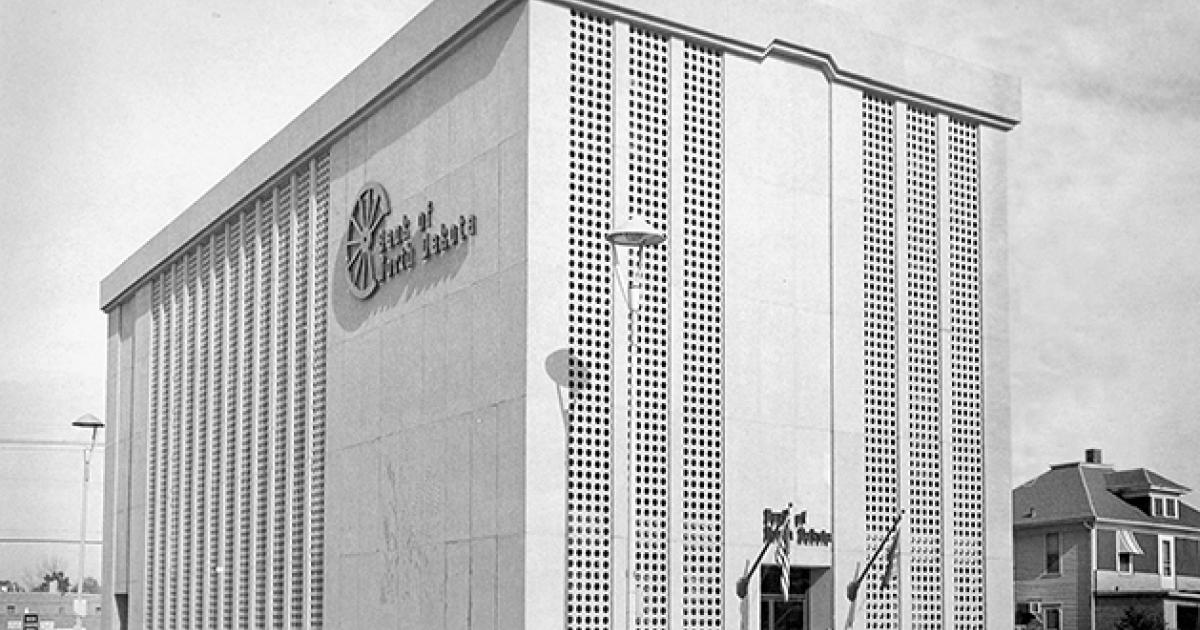

One hundred years ago, a bold social experiment began on the prairie, settling into its first form at the corner of Seventh and Main streets in Bismarck. The succeeding century would not come without its share of hurdles, but the will of North Dakota’s people would reign.

That social experiment was the Bank of North Dakota (BND), which celebrates 100 years in 2019.

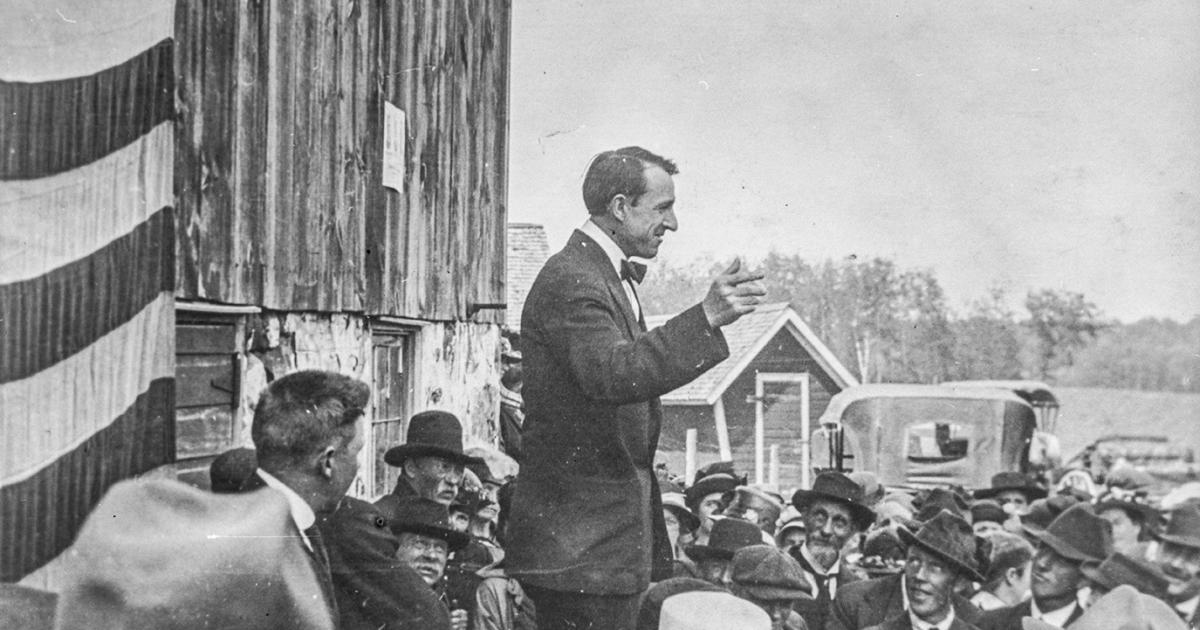

Arthur C., “A.C.,” Townley addresses a group of Nonpartisan League (NPL) members. Townley is credited with conceiving the NPL, which began as a discontented agrarian movement. The league was one of the early advocates for a state-owned bank. Photo: State Historical Society of North Dakota, B0921-00001

“We’ve always struggled out here on the prairie,” says Eric Hardmeyer, the current and 13th manager of the Bank of North Dakota. “It was that mindset that nobody’s going to look out for us except us, that feeling that we needed to take control of our own destiny. That’s what made the Bank of North Dakota.”

It was through the organized efforts of the Nonpartisan League, and the desire to protect the social and economic position of the farmer, that both BND and the North Dakota Mill and Elevator were established. As an ag-based economy, state ownership of these entities made it easier for farmers to make a living, no longer at the mercy of out-of-state grain dealers who suppressed prices, farm suppliers who increased their prices, or big-city banks that jacked up interest rates.

“It was kind of an angry agrarian movement. Folks felt like they were being taken advantage of,” Hardmeyer says.

And while BND grew from those agrarian roots, the bank has evolved over the years to meet the current needs of North Dakotans.

“What started off as an agrarian movement has evolved and changed into a larger kind of experience,” Hardmeyer says. “The ability to adapt and change to meet the evolving needs of the state – that’s really the beauty of the bank. It’s about looking around the corner.”

THE EARLY YEARS

The 1919 North Dakota Legislature provided the enabling legislation to start the Bank of North Dakota and required the new state bank be open for business within 90 days of adjournment. Also established during the 1919 legislative session, the newly formed Industrial Commission went to work immediately, fulfilling that duty. The bank opened its doors on July 28, 1919, with 46 employees and $2 million of capital.

After the dramatic changes brought forth by the 1919 legislative session, the Independent Voters Association (IVA) referred several bills, including that which created BND. A “bitter campaign, in which the IVA lied repeatedly to the people of North Dakota” ensued, as described on the BND microsite created to commemorate the bank’s 100th anniversary. By a 23,256-vote majority, the Bank of North Dakota was reaffirmed.

“I think (the referendum) was the critical early test. (The bank) survived.” Hardmeyer says. “The people said, ‘This still works. We still want to do this.’”

The Bismarck Tribune led its June 27, 1919, issue, the day following the referendum vote, with news of the victory, “‘Industrial Democracy’ Indorsed.’” North Dakotans had spoken, and the bank was here to stay.

THE GREAT DEPRESSION

Another test for BND came between 1928-1940 with the Great Depression and Dust Bowl.

“It was a bigger catastrophe in North Dakota than it was in Oklahoma, or Arkansas, or Kansas, or Nebraska, or even South Dakota,” says Clay Jenkinson, a well-known area historian and scholar, in a video reflecting on this period in the bank’s history. “We were thee epicenter of the Dust Bowl catastrophe, a man-made environmental disaster on the Great Plains.”

In 1935, one-third of North Dakotans were on direct federal assistance, Jenkinson goes on, and people needed a hero. That hero came in the form of William L. Langer, who took office as North Dakota governor in 1933.

It was Langer who pulled BND out of the state toolbox to help keep North Dakota going and save family farms. During this period, the Bank of North Dakota redeemed warrants against future tax collections, which local governments and school districts used to pay employees, at face value. Essentially, these were post-dated checks. Langer also helped shape BND policy, so that the bank would only foreclose on: completely abandoned land; lands controlled by court officials or heirs of property of mortgaged land that they were not occupying; lands not occupied or operated personally by bona fide farmers; or lands where the mortgagee agreed to the foreclosure in order to clear title.

“(Langer) used the flexibilities that were inherent in the Bank of North Dakota,” coupled with his own ideas, “to hold people on the land and to give them more time and patience than a commercial bank could have possibly justified,” Jenkinson says.

Langer’s actions during this period are believed to be the impetus that saved thousands of family farms in North Dakota.

AN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ENGINE

World War II and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs helped to pull America out of the economic crisis ushered in by the Great Depression and Dust Bowl. What followed was a relatively quiet time in BND’s history, until the 1960s, when Gov. William L. Guy changed course.

“Gov. Guy looked at the bank and said, ‘There’s more here that we can do with this institution,” Hardmeyer says. “He really was the one that set it up to become an economic development institution, which I think was a critical point in the bank’s history.”

In his first address to the North Dakota Legislature as governor in 1961, Guy said: “The philosophy of lending of the Bank of North Dakota should reflect our faith in the potential of economic development for our own people.” The bank should have “more latitude in financing industrial development.”

That same year after a 28-year hiatus, the bank started making farm loans again, which were guaranteed by the Farmers Home Administration.

Decades later, Gov. George A. Sinner echoed Guy’s sentiments when faced by another dark time in North Dakota. In the mid-1980s, the next farm crisis began and the second boom-and-bust cycle hit the oil industry. Sinner advocated for the bank to not only act as a lending institution, but a catalyst for community development.

“Gov. Sinner looked at the bank and said, ‘How can we use this to help, not only economic development, but diversification? How do we use this bank to start assisting with an economy that needs to morph away from just agriculture?’” Hardmeyer explains.

As a result, the bank began setting aside a portion of its profits to fund community development programs, like the PACE (Partnership in Assisting Community Expansion) program. Regarded as a successful public-private partnership for BND, $2.7 million was appropriated to fund small-town investments, and the bank worked with local commercial lenders to keep investment loan interest rates low.

STUDENT LOANS

Another largely active arm of the Bank of North Dakota has been its involvement in student loans. In 1967, BND started the first federally insured student loan program in the United States and has administered its own state-sponsored student loan program since 1997, to fill gaps when federal funding falls short.

But it didn’t stop there.

“One of the most important things we’ve done in recent history was to really understand the student loan debt picture,” Hardmeyer says.

In 2014, BND put together the first student loan debt consolidation program in the country.

“I remember talking to a woman who was working and looking to buy her parents’ business from them, but she was strapped with so much student debt that she couldn’t afford to move out of her parents’ basement,” Hardmeyer recalls.

Utilizing BND’s tools, this woman was able to consolidate her debt and refinance at historically low interest rates, which reduced her payments by over $300 a month. “And that’s when things really start to become available to people. Maybe they can afford a car payment or even rent,” he says.

INFRASTRUCTURE AND DISASTER RELIEF

In more recent history, the Bank of North Dakota has been a key funder of infrastructure projects and disaster relief.

When the Bakken oil play started to expand in 2008-09, it was apparent that infrastructure development was needed to support such growth.

“BND played a pivotal role in providing capital to an area that sorely needed investment, as these communities (in western North Dakota) did not have the infrastructure – traditional, hospitality or otherwise – at a sufficient level for the masses that came,” Hardmeyer says. “BND used its resources to work with the private sector to really help build that out.”

BND has also answered numerous calls from residents and communities struck by natural disasters over the past 20 years, starting in 1997 with the Grand Forks flood. More than $200 million has been dispersed from BND since, in partnership with local lenders, to help families get re-established after extreme weather-related events. Often, this funding is received before federal aid arrives.

“We have the tools that nobody else does. We’re able to address certain issues quicker with that readily available liquidity,” Hardmeyer says.

AN ANOMALY ON THE PRAIRIE

Today, North Dakota is the anomaly: It’s the only state in the country that operates a state-owned bank. Why is North Dakota such an outlier? Could it happen again?

“When I saw what happened after the Great Recession (2008-09), the backlash against the big banks and some of the state institutions, what I saw was some of the same kind of fertile ground that existed 100 years ago when we were created,” Hardmeyer says. “Can it happen again? Perhaps, it could. The headwinds today are much greater than they were 100 years ago."

THE NEXT HUNDRED

For a man who’s been with the Bank of North Dakota for a third of its history, starting in 1985 as a junior loan officer, there’s likely no better person to speak to the next hundred years than Eric Hardmeyer.

While impossible to predict the future, Hardmeyer looks for the bank to continue in its vigilance to meet the challenges of the day.

“I’m hopeful that we are mindful of the mission and the ability to make a difference. We are here to improve North Dakota, and if we’re not thinking about that every day, then shame on us,” Hardmeyer says.

One thing’s for sure: North Dakota’s history books would look different had this chapter never been written. Was it worth it? Time will be the judge. But for now, North Dakota’s bold social experiment – the Bank of North Dakota – stands tall amidst the prairie winds.

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.