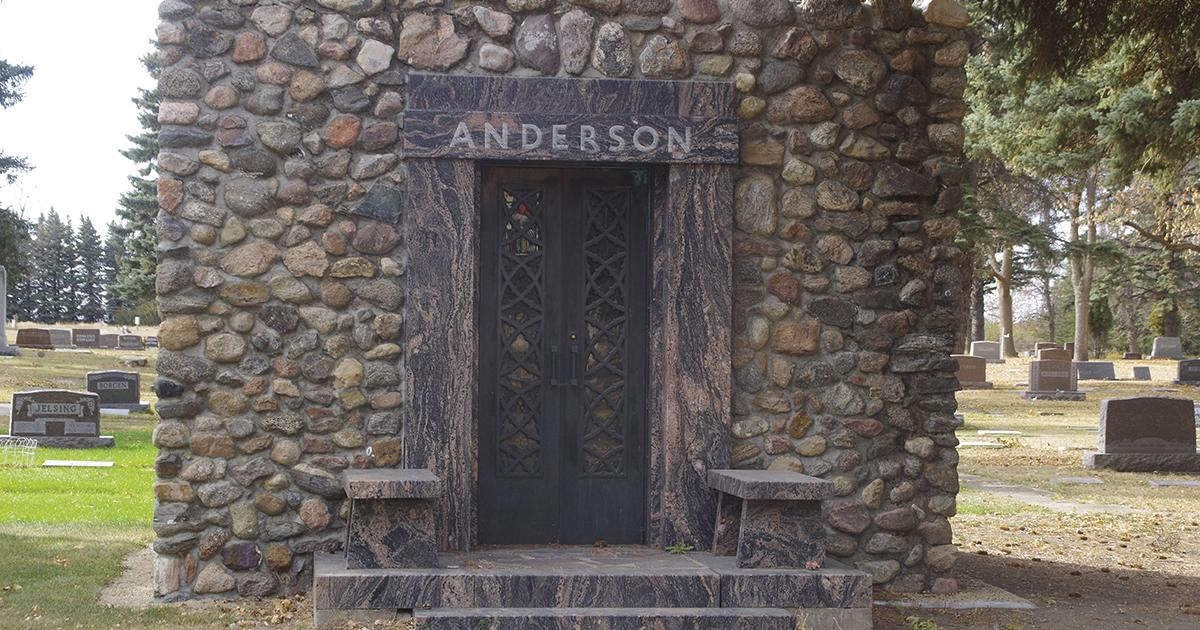

This Priscilla Watts Cemetery memorial chapel, an Anderson family mausoleum (top right) and rock wall (right) were built of fieldstone by Rugby funeral director John Anderson. Photos by Bill Vossler

John Anderson dearly loved rocks, judging by his lifetime of work with them. It wouldn’t be surprising if his mother had to empty his childhood pants pockets of stones before she washed his clothes, nor is it surprising he chose a career in stone masonry.

But the true test of his partiality exists yet today in the creative and beautiful work he performed with rocks – mere fieldstones – erecting exquisite functional edifices, making Rugby – and all of North Dakota – the richer for it.

A bit of history

John E. Anderson homesteaded near Rugby in 1900. While driving his matched team of bays pulling horse-drawn hearses to funerals for director W. J. Holbrook, he became interested in that profession.

After obtaining his embalming license, Anderson bought Holbrook’s business in 1921 and started the Anderson Funeral Home, now the oldest business in Rugby. By this time, he had heard complaints of farmers south of town quailing about the large number of rocks in their fields, breaking machinery and causing extra work.

Anderson had rocks on his homestead, too. But instead of viewing them as problems, he began to see all the area rocks as a solution. He needed a new funeral home, so he came up with the wild idea to build one – out of fieldstones. And not just any building, but a unique and artistic one.

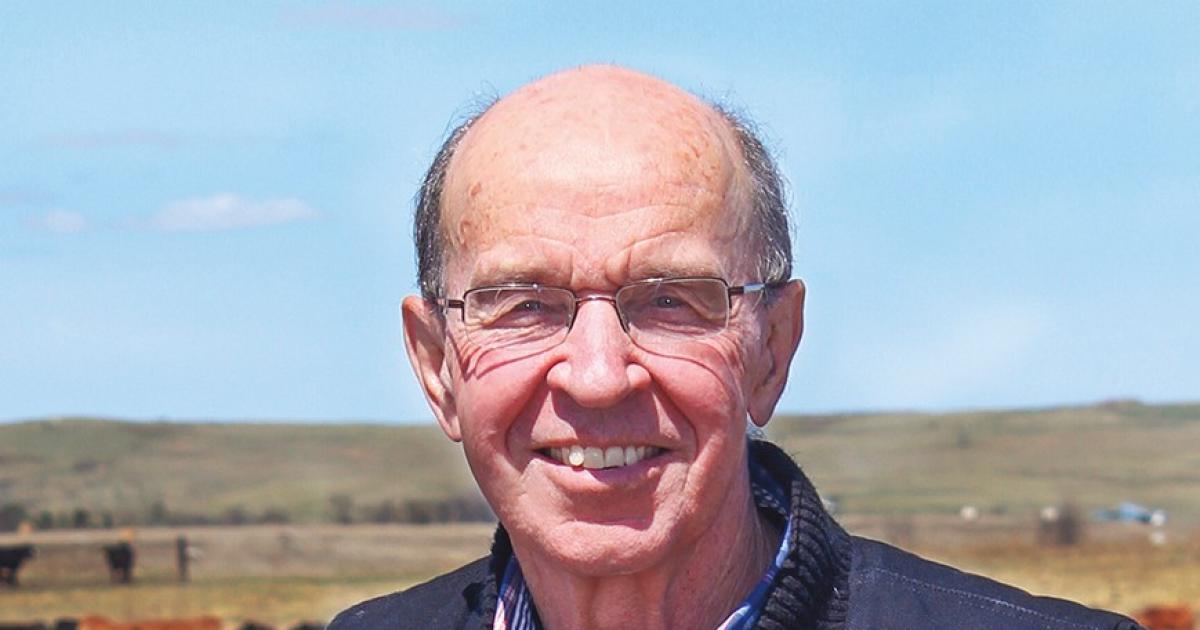

“John was an out-of-the-box thinker, so that’s how that idea came about,” says Hallie Anderson, fourth-generation Anderson Funeral Home director.

In the early 1930s, he announced his intention to build the funeral home out of fieldstone.

“When I was young, I heard about John from my mother. She said he was such a people person,” says Sharon Anderson-Stork, Hallie’s mother. “He drove around to the farms and visited, wanting to know everybody. He helped many farmers and community people whenever he could, no matter who they were, which made him a very well-liked man in the county. So, people were willing to help him with the rocks.”

There were many rockpiles around, plus farmers and friends picked rocks off the fields and brought them to John – many thousands, judging by the number of rocks needed to make just a couple of walls of the buildings.

John picked fieldstones, too.

“He went out to the farms, loaded them up and brought them to town, too. His son, Harold, helped as well, and the farmers were very happy to get rid of their rocks,” Sharon says.

By the mid-1930s, John followed through on his idea. He designed the funeral home’s structure, used his own masonry experience to construct it and finished it in 1936.

“He built most of it himself,” Sharon says.

|

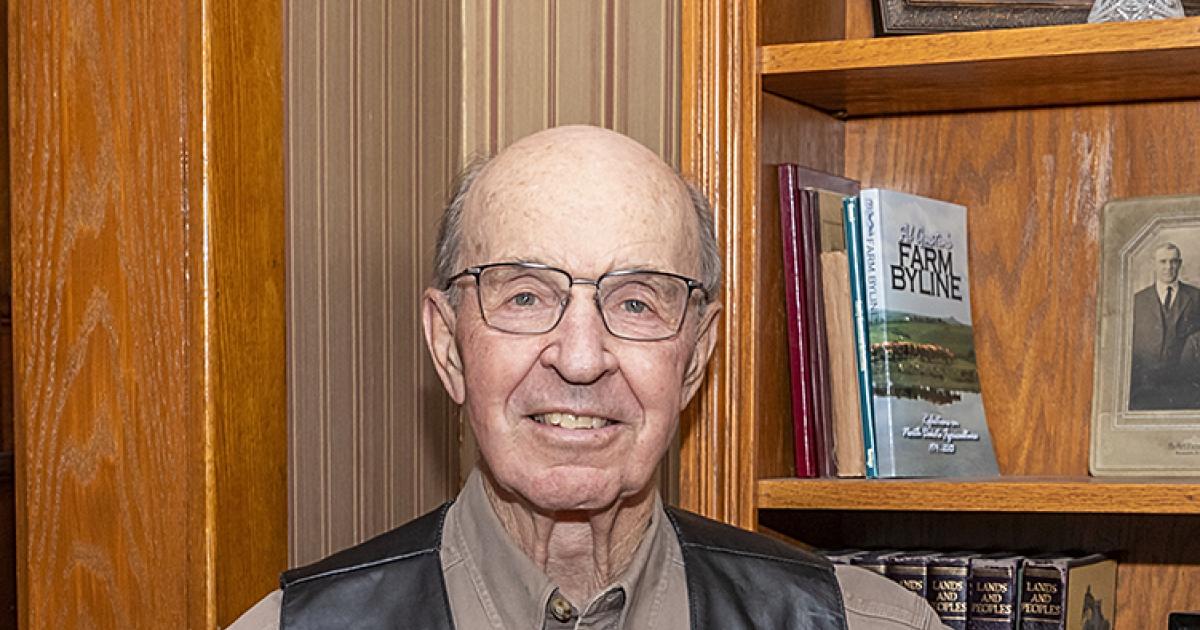

| Fourth-generation funeral director Hallie Anderson, her mother, Sharon Anderson-Stork, and Jon Stork of Anderson Funeral Home in Rugby sit on one of the walls John Anderson created of fieldstone almost 90 years ago. Over 600 fieldstones can be counted on the single front wall of the funeral home seen in the background, giving a sense of the large number of stones used in John Anderson’s works. Photo by Konnor Anderson |

More to come

John’s creativity didn’t end there. On the lot east of the funeral home, he made a second building out of fieldstone – even more stunning than the funeral home – a house for his son, Harold.

Further east, John built a second house of fieldstone for his son, Willard – a mirror image of Harold’s and just as eye-catching.

And when he was done, John built house number four for himself – an artistic round home of fieldstone. Though created of common fieldstones, the houses are beautiful works of art.

“I grew up here in Rugby, and before I was an Anderson, I remember my mom’s friendship group said that John built that house with no corners, because he didn’t want to be cornered,” Sharon says. “I don’t understand it all, but it is one of the odd things they talked about.”

Significance for many

Growing up, Hallie didn’t realize the fieldstone creations held special significance to people in Rugby and the surrounding area.

“I took them for granted. The house next door was just Grandma’s house to come to for a picnic in the summer between the two houses,” she says.

Hallie learned how significant the buildings were after moving back to Rugby in 2010, and later, working in the funeral home.

“After I bought Grandma’s house from my father, I thought it might have to be torn down,” she says.

But after hearing from people who loved the buildings, she decided it would be better to completely remodel the interior.

“In 2021 to 2022, I totally redid the inside of this house. Since then, I’ve gotten many comments from people in the community, saying how happy they are I am remodeling the house instead of tearing it down, or leaving it to fall apart. They’re also happy to see me staying in the community. I really hadn’t realized the significance of it all,” she says. “To this day, many people stop, roll down their car windows and take pictures of the buildings from the streets.”

“People not only randomly stop and take pictures, but also ask how this landmark in the community came about,” Sharon says. “Adults say, ‘I remember these houses, and marveled at them when I was a kid.’ Nobody ever forgets them. Even people passing through town stop and take pictures. Everyone is curious.”

During visitations and funeral services with returning extended family members, they remember the funeral home from their childhoods, Sharon adds.

“They remember seeing it and knowing the funeral home was so special. Their parents told them this building was kind of a family heritage, and it was something they always remembered,” she says.

Sharon says the buildings don’t require much outside maintenance, because they are so well-built, but the interiors require more work.

“The interior is original, so there is some upkeep, like mortar repair. Not often. Maybe a minor crack over the winter that needs repair. No rocks ever fall out,” she says.

“When people come inside the funeral home or houses for the first time, they are intrigued. They just can’t believe the buildings are so neat,” Hallie says.

Not only are these fieldstone buildings unique, but there is family history behind them, Sharon says. Only Andersons have ever lived in them.

Oddities

Considering funeral homes deal with the dead, some people can react strangely. For example, the tunnel between the funeral home and the first house was the site of odd occurrences, Hallie says.

“Grandpa Harold Anderson had many apprentices and sometimes they would do professional work at night. A couple of times when they entered the tunnel in the dark, they were scared by seeing the whites of somebody’s eyes, which turned out to be Harold, who walked through the tunnels at all different hours. These incidents caused a lot of talk, probably because it was a funeral home,” Hallie says.

Another oddity involves a piece of glass John mortared into the distinctive fireplace of the funeral home, along with other special stones he found in fields, Sharon says. The piece of glass, about 5 inches long and 3 inches thick, was one.

“In 1935, two cars collided head-on in a bad auto accident in rural Rugby, and knocked down an electric pole. The live wire fell on the cars, and the gravel road. Because everybody was killed, the electricity burned long enough to turn a 9- by 12-foot area on the road, and 3 feet deep, into glass. John held the funerals for those four people, and the glass in the fireplace is a remembrance,” Sharon says. “I never knew electricity could do that to a road.”

Other rocky work

John erected two more fieldstone buildings at the Priscilla Watts Cemetery in Rugby: an Anderson mausoleum and a holding chapel for those who could not be buried in the winter. With help, he built a solid block-long wall in front of the cemetery. Again, all out of fieldstones.

Continuing his labors of love with fieldstones, John built a birdbath in front of the funeral home and a grill behind one of the houses, with a seating area.

“There isn’t anything about these buildings that I don’t like,” says Hallie, a fourth-generation funeral director after John, Harold and Richard Anderson.

Her sentiments echo what others have said over the years after seeing these edifices, and learning about the grit, creativity and love of beauty they’re built upon.

They’re the legacy John created, and Andersons continue to sustain.

Bill Vossler is a freelance writer and author from Rockville, Minn., who appreciates small-town North Dakota stories and history. He saw the beauty of Rugby’s fieldstone buildings during his eight years writing for the Pierce County Tribune.