Rural communities concerned about property tax measure

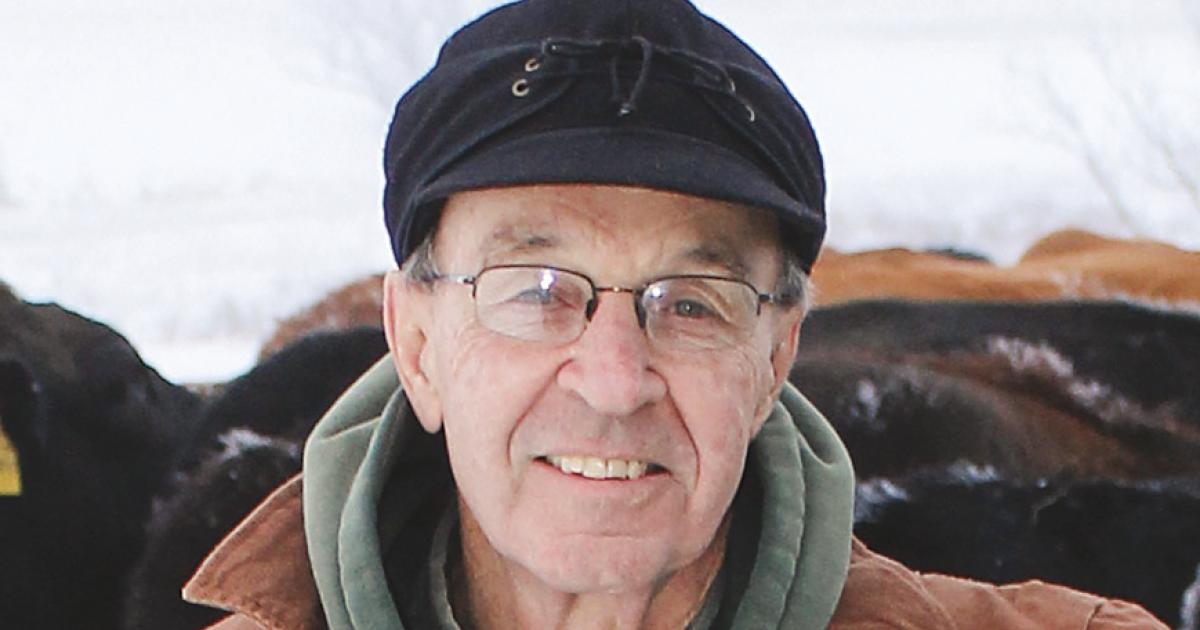

McKenzie County maintains about 1,500 to 1,800 miles of roads, which is roughly the equivalent of driving from Watford City to New York City or Houston, says Road Superintendent Layton Northrop. Photo by NDAREC/Kennedy DeLap

You could drive from Watford City to New York City and the distance would be roughly the equivalent of the miles of roads maintained by McKenzie County in the western North Dakota oil patch.

“It’s right around 1,500 to 1,800 miles of roads with gravel and pavement,” says McKenzie County Road Superintendent Layton Northrop.

Howdy Lawlar has driven most of them.

Farming in his tractor or feeding his registered Black Angus cattle.

Driving to county commission meetings as chairman or responding to calls as a volunteer fireman.

Heading to college at North Dakota State University on a football scholarship or returning home after his first teaching job in Berthold.

“Dad told me growing up, if you want to take over the family farm, you have to come back with a college degree,” Lawlar says.

He proved to his dad, Rick, he was a good listener, and the pair have been farming and ranching together ever since.

But it’s not the only job they have in common. Howdy is the second Lawlar to serve as chairman of the McKenzie County Commission. Rick is the first.

“Since I’ve been a commissioner, and my dad used to be a commissioner, we want to take care of the rural community,” Howdy says.

For Howdy, that means using his voice to share why the November ballot measure to eliminate property taxes is bad for North Dakota.

“That’s what I try to get people to understand, too, is that for every action, there’s a reaction. And it sounds good now, until ‘oh, there’s no money,’” he says.

SQUEAKY WHEELS

Informed by his knowledge and experience as an educator, volunteer firefighter, farmer, rancher, rural North Dakotan, county commissioner and community leader, Howdy enumerates many concerns over the ballot measure and its potential to negatively impact his community and state.

“Right now, we have two great worlds. We’re able to have the service and we’re able to have the infrastructure. And if we lose (property taxes), something has to give,” Howdy says. “We can’t let our infrastructure go, and that includes our roads, you know, our water and all that stuff. So, our service goes.”

In the winter, it takes McKenzie County road department workers three days to clear all the county roads. But if workforce and budget cuts are necessary, it could take triple the time, Northrop says.

“It’s scary to think of having to sit at our commission meeting and say, ‘OK, departments, you need to lay off 10 workers you need.’ I mean to sit down and say, ‘Here you go. You tell us who you want to keep.’ And we’re going to have to do it,” he says.

That’s Northrop’s biggest fear.

Having first worked for McKenzie County when there were 15 or 20 road crew members by his estimation, Northrop now oversees a crew of about 50 people in a county road department with a proposed 2025 budget of $107 million.

“If they cut our budget even in half and start taking employees away from us, you know, there’s a lot of squeaky wheels out in the area. They think it’s bad now, just wait if this (property tax elimination measure) goes through,” Northrop says. “It’s pretty spooky for me. The biggest thing that scares me is losing my guys, because we’ve got such a good group of guys here that mesh together so good. (It’s) hard-working and a lot of down-to-earth people that come here from other places and set roots, then kind of get the rug pulled out from under them. That’s what I’m really afraid of.”

THE PLAN, OR NOT THE PLAN

The property tax measure – Measure 4 on the general election ballot – would prohibit political subdivisions – including cities, counties, townships, schools and park districts – from levying property taxes on assessed value. It would also require the state to provide annual property tax replacement payments to political subdivisions in the amount levied in 2024, which is estimated to be $1.329 billion per year.

The measure leaves it to the Legislature to determine how to make up the replacement revenue, by cutting programs, jobs or other general fund expenditures to the tune of $2.464 billion for the current biennium. That’s 40.4% of the 2023-25 general fund state budget.

Literature from the measure proponents, the End Unfair Property Tax group led by former Rep. Rick Becker, whose attempts to get a similar measure through the Legislature failed in 2021 and 2023, insists there will be “NO loss of funding” and “no need to cut any service or staff.” It also says the state can “easily replace” the local property tax funding without raising taxes or cutting services.

“The one thing that you never hear from (Becker), though, is how they plan for the state to compensate local governments. … The proponents will say these are ‘scare tactics’ and that everything will be fine, just trust them. But there is no plan. Saying the Legislature will take care of it is not a plan. Saying the Legislature will magically find the $1.329 billion annually to cover our schools and emergency services is not a plan,” says Chad Oban, chair of Keep It Local, a coalition of more than 80 groups and member associations that have organized to oppose the measure.

Local political subdivisions will be left to figure out new fees, special assessments and taxes on local citizens to fund essential public services beyond or above 2024 levels, perhaps when needed to build a new school, buy a new firetruck, improve a road or adjust for inflation.

“We’re not going be able to maintain our fire departments,” Howdy says. “If we have truck trouble, we can go to the county commission and say, ‘Hey, we can’t quite afford this. Would you mind kicking in some money?’ And we could say, ‘Yeah.’ Where now, it’ll be we can’t. We have to go to Bismarck and lobby for money.”

Devising new taxes or fee structures is burdensome and could disproportionately affect rural communities, which often don’t have the population or traffic to generate meaningful revenue through income or sales tax.

The measure also discredits the efforts local governments have made to keep taxes low or cut spending.

“What county folks don’t get credit for is that there were counties that reduced their budgets. In fact, from 2021 to 2022 counties saw a decrease of 1.2% in property taxes collected,” says North Dakota Association of Counties (NDACo) Executive Director Aaron Birst, noting the Consumer Price Index grew from 4.7% to 8% in that time.

McKenzie County had the lowest average mill rate by county in 2022, according to the N.D. Tax Commissioner’s 2022 Property Tax Statistical Report.

“We’ve really tried hard to keep our property tax down. Why? Because it’s been what’s kept McKenzie County going. It was ag based. That’s what kept our stores open. It was the locals, you know. We were here doing our stuff to keep things open, and so we’ve pushed to keep our property tax down,” Howdy says.

Revenue from oil and gas production taxes (GPT) that filters into McKenzie County has helped keep property taxes down. The county averages $75 million annually in GPT revenue, compared to the $6 million it receives in property tax revenue, of which more than half is paid by the oil companies.

“Our goal (as a county) has always been to have lower property taxes, because we want people to come to our area. We want the farming industry to stick around. Because if everything goes away, I mean, let’s just say the oil just said we’re done. You’re still going to have the guys that are putting seed in the ground, that are going to town and buying their stuff locally, doing things locally,” he says.

What’s also worrisome in McKenzie County is the risk of a funding formula change. If the state were required to provide property tax replacement payments to political subdivisions, what’s stopping the Legislature from tapping into the GPT pot?

“GPT, as well as Operation Prairie Dog funds received by non-oil counties for infrastructure like roads, are certainly at risk of being reallocated to fund budgets in other parts of the state,” says McKenzie County Auditor/Treasurer Erica Johnsrud.

TOO HIGH, OR NOT TOO BAD

There is no denying North Dakotans fall in both camps when it comes to property taxes. Many have been committed for years to ending what they believe is an unfair tax. Others don’t like paying property taxes, but look around their communities and see their property tax dollars at work – in schools, libraries, roads, snowplows, parks, emergency medical services (EMS), law enforcement and public safety.

“When I write a check out for (my property taxes), I’m like, wow, all the stuff you get … this is, it’s a deal. It really is. It’s a good deal,” Howdy says.

“What’s nice about (property tax) is we have absentee landowners that don’t live here, but they’re still paying that tax. That also helps with our fire, our EMS, our sheriff’s department,” he adds.

A figure from the NDACo illustrates how North Dakotans value and support their local communities. In the 2022 and 2024 election cycles, voters approved 52 of the 57 county ballot measures to add or increase levies – a 91% approval rating.

“We farm and ranch, too, and in McKenzie County, North Dakota, our property tax really isn’t that high,” Northrop says. “This property tax measure idea, I just don’t understand the logic of thinking. Personally, you know?”

___

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.