3D-Fuel’s printed samples of its offerings in color filament.

Courtesy photos

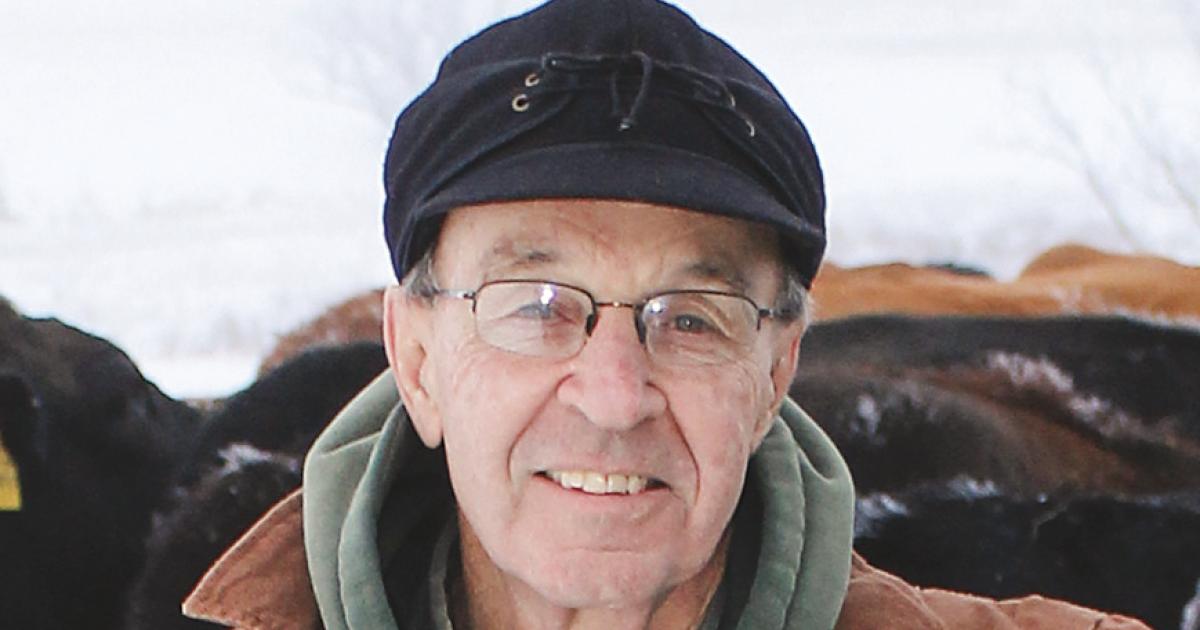

John Olhoft and John Schneider share more than a first name. Both are ensconced at the epicenter of the 3D printing universe.

As president of Fargo’s LulzBot and its parent company, FAME 3D, Olhoft leads the largest 3D printer manufacturer in the United States.

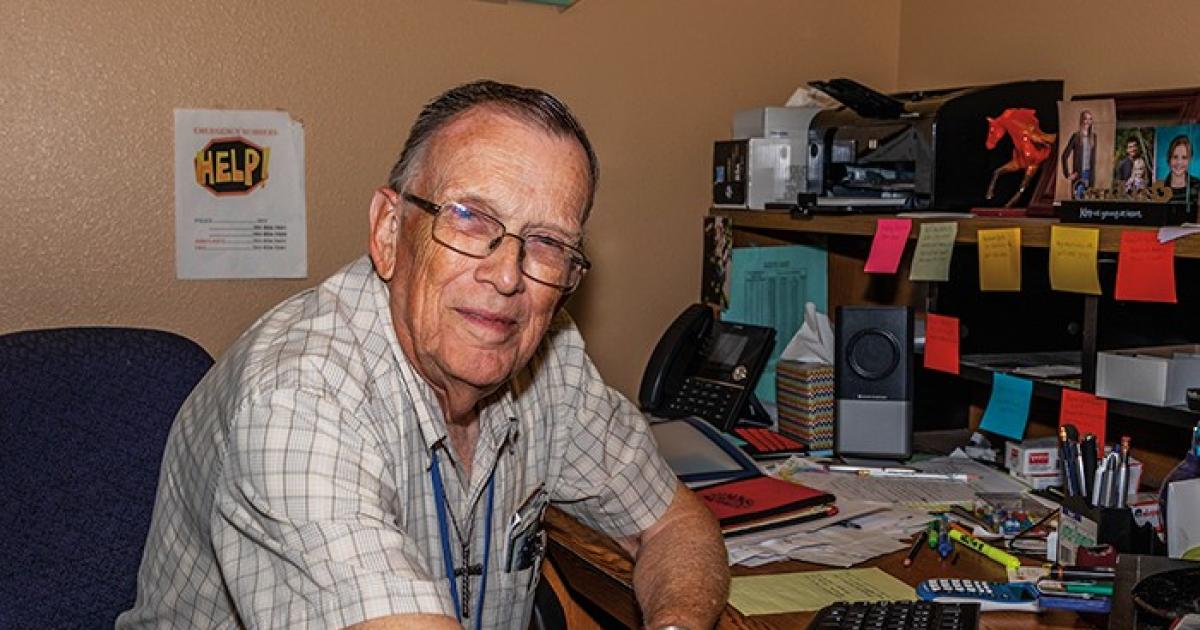

At another Fargo company, co-founder and CEO of Fargo 3D Printing and 3D-Fuel, Schneider leads a team who has developed 3D printing filament not found anywhere else in the world.

What is 3D printing?

Three-dimensional printing is a process that builds layers to create a 3D object, using a digital model created with computer-aided design (CAD) software.

In simple terms, the printer is a robotic hot glue gun. The raw material, in the form of filament, is fed into the printer, heated and extruded in a certain pattern to create a product. Those using 3D technology can design a specific object, then print it in plastic, resin or even sugar. Or an existing product can be scanned and replicated with a 3D printer.

The fuel guy

Fueling 3D printers is Fargo-based 3D-Fuel, a company with global connections and local roots.

A 2012 North Dakota State University (NDSU) graduate with a marketing degree, Schneider was a tech entrepreneur exploring options after college, when 3D printing blinked on his career radar.

In January 2013, he purchased his first 3D printer in the form of a $400 kit.

At the time, more substantial printers cost thousands, so he formed the idea of sharing ownership of printers in a makerspace. A business based on that concept was formed – and failed. But it led Schneider to meeting Jake Clark.

The two young entrepreneurs – Clark and Schneider – launched Fargo 3D Printing in 2014. More network connections led the two to Danny McMenamin, who was manufacturing filament in Ireland.

In 2016, an umbrella company, 3DomFuel Inc., was formed by merging three organizations, including the Irish manufacturer, into what is known publicly as 3D-Fuel in Fargo. McMenamin is director of research and development, working out of a production facility in Moville, Ireland. Fargo 3D Printing, which sells printers and parts, was also folded under 3DomFuel Inc.

“We definitely struggled. We had a lot of learning opportunities that happened throughout the years,” Schneider says.

Today, 3D-Fuel has found its niche, manufacturing quality, unique filament.

“When you take a look at a spool of it, frankly it looks like glorified weed whacker string,” Schneider says.

The manufacturing process starts with PLA material in the form of plastic beads. Combined with color pellets, the PLA is carefully heated and melted in the extruder (a long horizontal barrel with a similarly long screw to drive the material forward), then forced through a die, similar to a Play-Doh mold forming a shape, Schneider describes.

A laser scanner precisely controls the diameter of the filament, which is an important step, Schneider says.

“It’s important that diameter stays consistent throughout that entire spool,” he says. “We were the first people in our industry to take the diameter tolerances seriously.”

The finished product is sold as a spool of filament weighing about 2.2 pounds.

3D-Fuel manufactures seven different filaments in about 40 colors, with plans to add more materials and colors. Recent additions, based on customer requests, are a glow-in-the-dark filament, desert tan and castle gray.

“Our most popular color is still black,” says Dirk Monson, marketing and eCommerce manager.

The corn-based PLA has the most color options. PETG is similar to medical-grade resin also used in food packaging. Another type is ABS. And a composite material infused with fiberglass strands provides additional rigidity and strength.

From farm to filament

Uniquely, the company also uses wastes from other industries to create filament with bio-based materials. Hemp from Montana is one of those products.

“We are one of the only companies that offers the hemp 3D printing filament,” Schneider says.

And 3D-Fuel is the only company in the world with a commercially available beer product, Monson says.

A coffee-filled filament is created with waste from a roaster in Fergus Falls, Minn., and a beer-filled filament is formed with waste from a malting plant in Moorhead, Minn. And, yes, coffee and beer aromas fill the air when the filaments are being heated during printing.

“They’re just unique. They’re fun materials to print with. There’s no real performance advantage to those,” Schneider says.

But they do offer other advantages.

“It’s another way to use an agricultural input that would otherwise go into the landfill or be tilled back into the ground,” Monson says. “The goal with those products is it’s more of a case study in how you can use other materials without degrading the quality of the product that we produce. From an agricultural standpoint, we’re really just trying to figure out what types of materials that we grow right here in this area or process can be used to add to another product that we’re using and making right here in this area and that would be our filament.”

“It allows us to stretch the virgin PLA resin material a little further,” Monson says, by using an agricultural product. “Which is an interesting and unique approach.”

3D-Fuel also works with another Fargo company, c2renew, to create those bio-based pellets used in the manufacturing process.

Courtesy photos

The PLA itself is corn-based, processed in Blair, Neb. “It’s a very, very high likelihood that North Dakota-grown corn is ending up in the PLA material that we’re then manufacturing into filament in Fargo,” Schneider says.

“We are as close to 100% made in America as you can get,” Monson says. “Even our cardboard is made just across town. Our spools are made in Massachusetts. Our input comes from Nebraska. … That is one of the things that really separates us. … I don’t know if there are other U.S. manufacturers that are that committed to the supply chain to be as U.S.-based as possible, and that’s really set us apart in the last 18 months.”

The printer guy

Olhoft, who graduated from NDSU in 2017 with a Bachelor of Science degree in agricultural and biosystems engineering and is now pursuing an MBA, knew little about 3D printing in college, until a fraternity friend utilized a homemade 3D printer to replicate a miniature boat.

“And my mind was blown,” Olhoft says. “The next day, I went over to Fargo 3D Printing and I said, ‘You’re hiring me. I need to learn more about this.’”

He worked part time at the company fixing 3D printers, then took a winding path back into the industry after college.

He started his first company in 3D printing, Fargo 3D Printer Repair, in 2018 with his father and NDSU senior lecturer, Matt Olhoft.

In November 2019, Olhoft and two partners, Cooper Bierscheid and Ron Bergan, formed FAME 3D to purchase the LulzBot brand’s assets.

They packed those assets on 28 semis in Loveland, Colo., and moved the company to Fargo, opening in the new location Jan. 1, 2020, and building the first 3D printer two weeks later.

“At this point, we are the biggest and one of the only desktop 3D printer manufacturers in the U.S.,” Olhoft says.

The company has five different model lines, along with the LulzBot Bio that replicates organic matter such as soft tissue for medical purposes.

“This past July, we launched a brand new printer that is 100% Fargo-designed, Fargo-built. We do all business operations here in Fargo,” Olhoft says. “Our newest model is interesting, because it’s the most affordable printer we’ve ever made, so we’re hoping for a lot higher volume on that line.”

With just over 75 employees, LulzBot utilizes an onsite print farm with 300 printers to manufacture many of its own parts to, in turn, build its printers.

The company 3D prints 500 line items for its own manufacturing process. LulzBot can create about 50% of its 3D printers by manufacturing its own parts, which illustrates the benefits of 3D printing.

Under the FAME 3D umbrella now rests LulzBot, Fargo 3D Printer Repair and Protosthetics, which 3D prints prosthesis and orthotics, working with clinics to scan an amputee’s limb and produce molds or a final piece for a more accurate organic shape.

With those types of applications, the world of 3D printing is endless, Olhoft points out.

“I think it’s set for some pretty explosive growth yet again. During COVID, you saw the need to make a lot of things fast. People illustrated their 3D printers could be used in that manner. We’re also entering a time where there’s a lot of supply chain shortages and the one thing we haven’t had to do is slow down,” Olhoft says.

“If I was relying on a network of 30-some vendors to get those 500 different parts, I would be very nervous right now. As long as I have raw plastic, I can turn it into whatever I want,” Olhoft says. “That is an invaluable tool that I think manufacturers will continue to see the value of, especially in times of supply chain uncertainty, if they know they can make it in-house.”

LulzBot’s clients include universities, schools, the military, hospitals and large manufacturers, such as Tesla, John Deere and Ford, as well as hobbyists.

At the cornerstone of 3D printing, Olhoft points to only one other place in the world, in China, where 3D printing is as pervasive as in Fargo.

More dimensions

Like LulzBot, 3D-Fuel and Fargo 3D Printing found opportunities during the pandemic.

“When we really started growing was in 2020,” Schneider says. “The pandemic presented some interesting opportunities for us.”

“In 2020, there was such a shortage of personal protective equipment that everyone that had a 3D printer was looking to jump in and help,” he says. More people also started 3D printing as a hobby or even a side business, and users looked to the Fargo businesses for assistance in launching their own 3D printing business.

3D-Fuel started with one production line in 2016 and has now grown to four production lines, adding two lines in the past year alone.

From college campuses to architectural firms, 3D printing is constructing an entirely new dimension for learning and creating in North Dakota.

“We have partnerships where they’re teaching 9 year olds how to 3D print right here in Fargo,” Monson says. “You’re starting to see this blossom where it’s not a fringe hobby. It’s becoming mainstream.”

Fargo 3D Printing focuses on getting people started and continue printing, Schneider says, and being a local resource. The company assembles and calibrates printers, so customers can have a printer that works right out of the box.

“The other area where we do really well is in the customer education and customer support side of things,” Schneider says. Customers can contact the company and speak with someone directly who has 3D printing experience.

For the entire 3D universe, Fargo has been welcoming.

“We have quite the 3D printing ecosystem in Fargo,” Schneider says. “In 2014, we were definitely before our time.”

“It is very welcoming to entrepreneurship,” Olhoft says. “North Dakota’s been a good state to do a business in. … In Fargo, it’s very easy to contact people. Somebody knows somebody. It has more of a small-town feel.”

“It’s been a pretty adventuresome journey,” Olhoft says.

Luann Dart is a freelance writer and editor who lives in the Elgin area.

3D printing class first of its kind at NDSU

A course focusing on 3D printing was offered for the first time last fall through the Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering at North Dakota State University (NDSU), which offers three academic degrees: agricultural and biosystems engineering; precision agriculture; and agricultural systems management.

The course is now in the final stages of approval to become a permanent course, to be offered as Ag Systems Management 234, “3D Printing and Manufacturing.”

This is the first course at NDSU dedicated solely to 3D printing, being taught by Matthew Olhoft, a senior lecturer in the Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering, which has seven 3D printers available to students. Olhoft has been involved with 3D printing for several years and recently attended a major conference on additive manufacturing.

“There is a need for our young engineers coming out of NDSU to be more aware of what they can do with additive manufacturing. … There’s just a lot more flexibility and the cost factors tend to be a lot cheaper, especially for producing prototype parts, with additive manufacturing,” Olhoft says.

The class starts with a brief history of 3D printing, then moves into the different types of 3D printing and the different materials that can be used. It then explores the process of printing, from designing a project to printing the product. A poll of the current class showed about half have 3D printed something before, while half are new at it, Olhoft says.

“3D printing is starting to get pervasive in our society in all kinds of levels. In the not-too-distant future, a lot of the parts that you need for machines will probably come to you via the internet. You’ll purchase an STL file and then you’ll actually print the part at your location or a local business,” Olhoft says.