Story and photos by Craig Bihrle

The intent of the outing, like that of many fine September Sundays with dog and shotguns riding quietly in a pickup’s backseat, was the chance to bag a sharp-tailed grouse.

The chosen destination, on this second day of grouse season last year, was a couple of contiguous sections of native prairie grassland that my partner insisted was always good for a sharp-tail or two, based on his experiences of covering it on foot many times over the years.

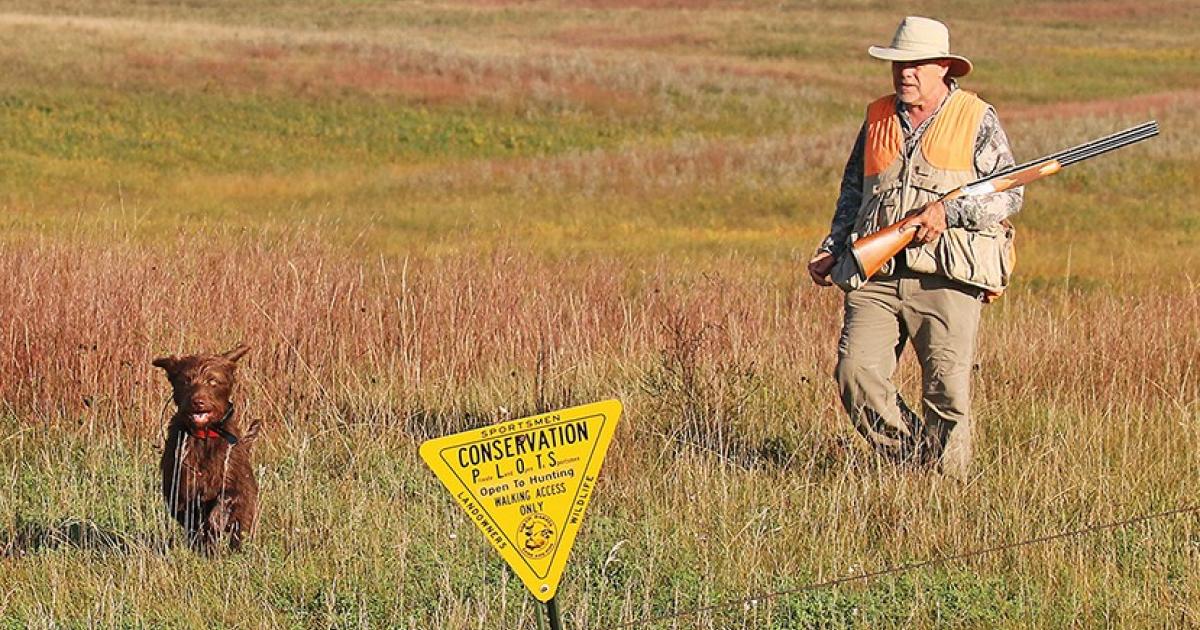

A man and his best hunting companion enjoy the beauty of a fall bird hunt.

But the similarities between this day and those of year’s past ended at the yellow, inverted triangular sign indicating the prairie we were about to explore was part of the N.D. Game and Fish Department’s Private Land Open to Sportsmen, or PLOTS, program. Which means, in essence, that a cooperating landowner had voluntarily agreed to open the property to walking hunting access in exchange for a lease payment that would add to the operation’s bottom line at the end of the year.

PLOTS program

This particular piece of prairie was enrolled in a sub-program of PLOTS called Working Lands, which allows the owner to continue whatever farming practice is taking place, typically under a shorter-term contract such as two or three years. In this case, that farming practice was cattle grazing, as evidenced by a few dozen Angus stretched out across a hillside southwest of the direction we were heading.

Of the roughly 800,000 acres in the North Dakota PLOTS program this fall, up from about 790,000 acres last year, more than half fall under the Working Lands designation and a good share of those agreements involve grasslands grazed by cattle. If the individual rancher’s grazing plan calls for it, the cattle are still grazing when hunting seasons start.

Kevin Kading, Game and Fish Department private lands section supervisor, says biologists meet with landowners interested in enrolling grasslands into the PLOTS program, to make sure they are comfortable with the potential for hunters on those areas.

“Most landowners are fairly open to that,” Kading said, adding that if they’re concerned about certain areas, they just won’t enroll those, while keeping surrounding areas in the program. “We haven’t experienced many issues really. … Hunters, I think, just naturally know to steer clear of areas where cattle are present.”

The ability to pick and choose options that can make a PLOTS agreement work, Kading said, is a big reason the program remains popular, with more than 2,000 landowners participating this year. “The program isn’t just one size fits all,” he said. “It can be tailored to fit just about any landowner’s operation.”

“All things considered,” Kading said in reference to the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on many aspects of life in North Dakota the last several months, “I’m really pleased with where we’re at.”

All of those acres open to public access this fall are included in the 2020 version of the PLOTS guide, now available in print form at many retail outlets around the state, and in electronic form on the the Game and Fish website at www.gf.nd.gov(link is external). Landowners interested in more information on how a PLOTS agreement might fit into their operation can find contact information for local private land biologists also on the website.

The hunt

Now, back to the grouse hunt.

In a normal fall, much of North Dakota’s sharp-tail hunting takes place on grazed prairie, which is a patchwork of short and longer grasses depending on grazing patterns. That was not the case on the PLOTS tract we entered. Once across the fence and settling into the random pace of a grouse walk behind a meandering bird dog, the influence of 8 inches of rain in that region from Aug. 1 to the grouse opener on Sept. 14 was remarkable.

Prairie grass grew tall and lush, to the point that a good share of it was more suited to pheasants than grouse. We eventually started concentrating on areas where the grass was less dense. Just such a patch produced the only flush we encountered, but like grouse often do, they launched just a bit out of shotgun range.

Despite no grouse for the morning, it was still a memorable day. That prairie landscape was alive, more like late June than mid-September. Late summer wildflowers like asters, dotted blazing star, remnant prairie coneflowers and goldenrod attracted pollinators of all sorts. Monarchs and bumblebees flitted from plant to plant in numbers enough to prod a hiking grouse hunter to purposely stop and take the time to observe more closely.

Some days afield are like that, when the experience overshadows the weight in the game bag. Fall is here, and the opportunities for just such a day in North Dakota are almost endless. n

Craig Bihrle is a freelance writer and photographer from Bismarck.