Cally Peterson

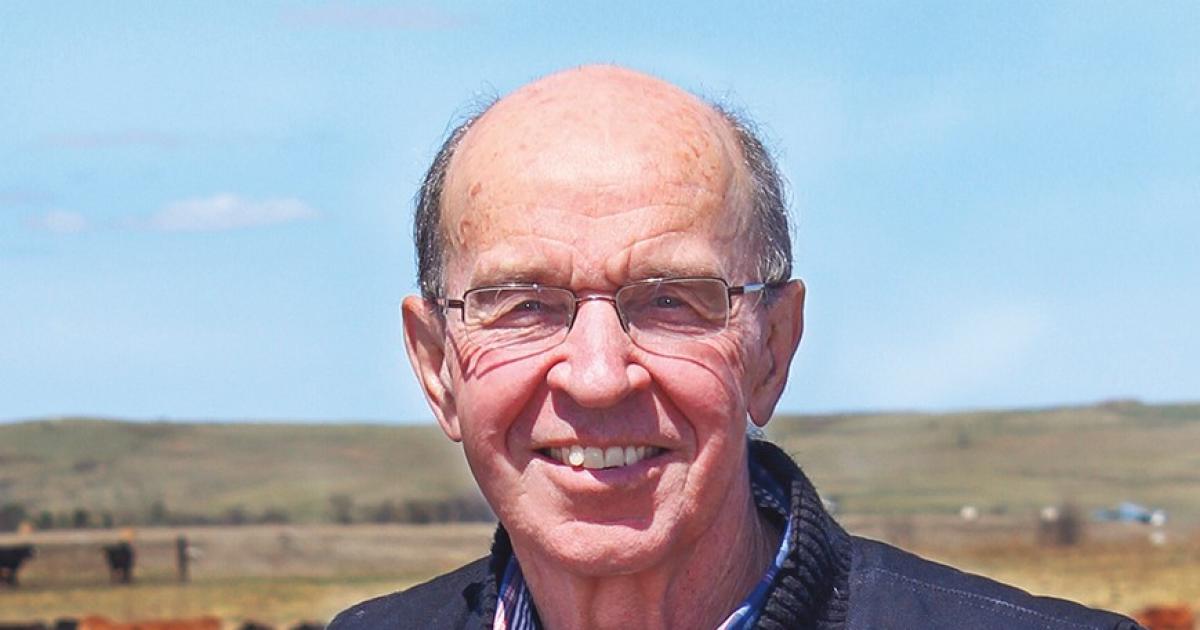

Jenee Munro said hello to North Dakota 10 years ago, and she has no plans to say goodbye.

Jenee Munro said hello to North Dakota 10 years ago, and she has no plans to say goodbye.

The Plentywood, Mont., native appreciates the wide-open spaces, abundant outdoor opportunities and natural wonders North Dakota offers. What’s more, she’s found a community she loves in Rolla, and one she says cares about her family, too, including her husband, Josh, and their three children.

Millions of Americans tuned in to the first “Monday Night Football” broadcast of the year. Two NFL powerhouses, the Cincinnati Bengals and the Buffalo Bills, faced off in a Jan. 2 game the oddsmakers had tipped in the Bills’ favor by two-and-a-half points. According to preliminary ratings, the game was the most-watched “Monday Night Football” telecast in ESPN history with 23.8 million viewers, surpassing a 2009 Packers-Vikings game in which many Upper Midwesterners likely were among the 21.8 million viewers.

It was not the game, however, that drew the massive audience.

If “rural electrification” was a buzzword spreading across the nation in the 1930s, “beneficial electrification” might be a buzzword of the 2030s.

Rural electrification in North Dakota held dreams of making life better for every farm family, and eventually, meant serving members in every pocket of this state, from the most remote to urban areas.

“A child care crisis.”

That’s how Gov. Doug Burgum described the state of child care in North Dakota, speaking at a press conference in September 2022 to pitch his child care plan.

“In many cases, parents have to choose between working and paying for child care, or not working at all,” Burgum told the Legislature in his executive budget address in December. “Currently, child care costs account for 15% to 40% of the average household budget in North Dakota, which often isn’t sustainable for young working families.”

From Pearl Street to the Pierson farm. From New York to near York.

On Sept. 4, 1882, Pearl Street station, Thomas Edison’s complete direct-current electric system, was publicly unveiled in Lower Manhattan. Edison’s electric idea eventually reached North Dakota farm country, where the Ray and Evangeline Pierson farm, 3.5 miles south of York, was energized by Baker Electric Cooperative on Thanksgiving Day 1937. It was the state’s first farm to receive electricity.

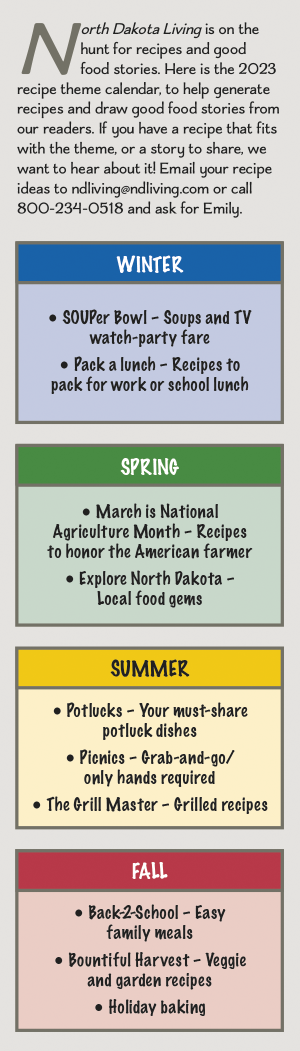

Thank you for faithfully sending the magazine from the local electric cooperatives. I especially appreciate the section on recipes.

Thank you for faithfully sending the magazine from the local electric cooperatives. I especially appreciate the section on recipes.