Commodity prices. Weather. Crop yields. Machinery breakdowns. Family obligations. Operating loans. Commodity prices. Weather. Crop yields...

Every day, this repetition plays on loop in the minds of farmers and ranchers, with many more thoughts sprinkled in. The pressures of farming and ranching are not new. But changes in agriculture and compounding factors have contributed to a new dialogue centered around farm, or rural, stress.

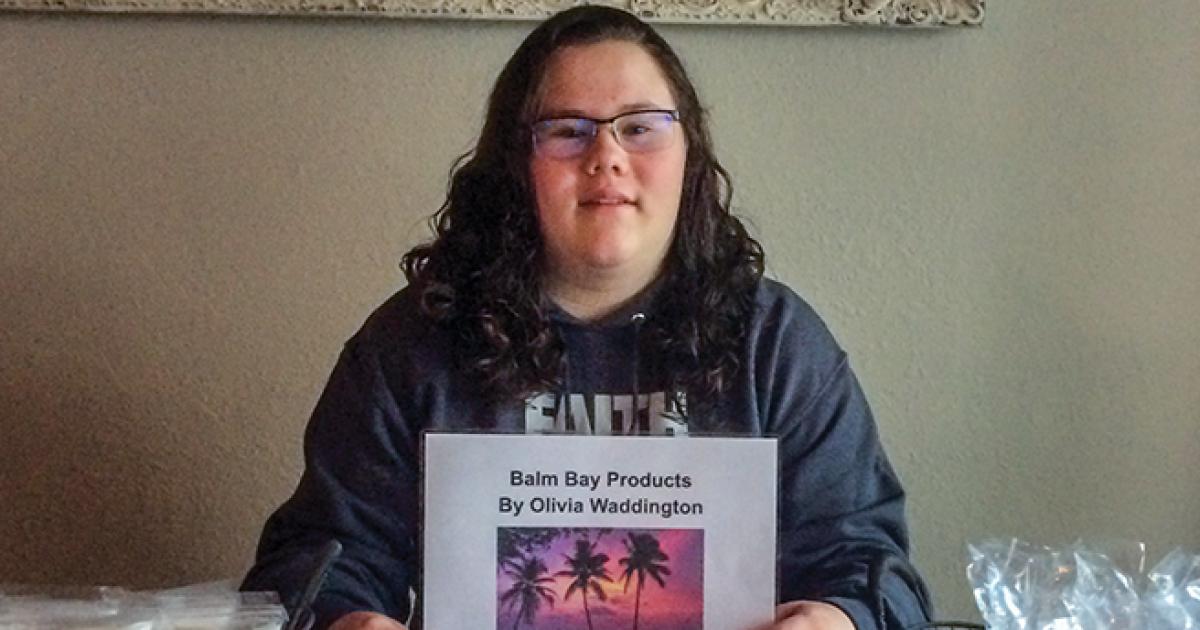

Becky Kopp-Dunham conducts therapy sessions via video chat, allowing farm families dealing with stress to access therapy services at home. Photo by Cass County Electric Cooperative/Sara Erickson

“Stress for farmers and ranchers isn’t new,” says Becky Kopp-Dunham, a licensed independent clinical social worker and farmer herself. “It’s the sustained level of stress (now) that makes it different. This has kind of been a perfect storm.”

A PERFECT STORM

The National Safety Council lists agriculture as one of the two most hazardous occupations. In addition to the physical danger agricultural occupations pose, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found that individuals working in agriculture often face stress-related conditions, such as hypertension, heart and artery disease, ulcers and nervous disorders.

“We’re in our sixth consecutive year of depressed farm income with net farm income expected to be almost 50 percent less this year than in 2013,” says North Dakota Farmers Union (NDFU) President Mark Watne. “Every farmer in the state has been impacted by the trade war and low commodity prices. This situation isn’t sustainable. We need things to turn around and soon.”

“Culturally, we are used to making things work. Farmers are so amazing at troubleshooting,” Kopp-Dunham says. “But there’s things affecting farmers that are outstandingly out of their control, and they can’t fix it this time.”

North Dakota State University (NDSU) professor Sean Brotherson, who has done much research on the topic and co-chairs the farm stress response effort at NDSU Extension, says the financial situations of both the farm and the family are key sources of rural stress. Brotherson lists the following as sources of farm financial stress: net farm/ranch income decline; meeting debt payments; cash flow on the operation; arranging financing; and complicated or strained decision-making. Sources of family financial stress include: the ability to meet family living expenses; balancing work and family; long hours; working multiple jobs; sense of inadequacy due to economic difficulties; and the generational legacy or facing the challenge of having to leave the farm.

That generational legacy is one stressor unique to farming and ranching, says Kopp-Dunham. A farming or ranching profession is not one someone can easily get into; it’s often passed from generation to generation. Multiple generations of families are also farming together and must operate at the crossroads of business and family. There is an enormous responsibility, and stress, that comes along with that generational model of a family farm or ranch.

“Multiple generations have been on that land, farming and ranching, and you’re the one that can’t pull it off,” Kopp-Dunham says, illustrating the impact a generational legacy can have on the next generation of producers. “What other profession is like this? How do you even compare that?” Kopp-Dunham asks.

It’s not as easy, then, as farmers and ranchers “just getting another job,” Kopp-Dunham explains. “It’s their way of life. You don’t just pick up and change a way of life.”

WAY OF LIFE

Because farming and ranching is a way of life, the pressures of the profession do not stop with the farmer or rancher himself/herself – it affects the family structure.

Brotherson describes the cyclical nature of stress, and how it ripples through a family or community, in an online presentation entitled, “Understanding Key Stresses in Farming and Ranching,” available through NDSU Extension. Ag pressures contribute to farm and family financial stresses, which affect the physical and emotional health of an individual. Those personal stresses can create relational stresses or conflict, which ultimately impact children, communities and more.

“Stress absolutely ripples through a family,” Kopp-Dunham says.

ONLINE THERAPY

Recently, a collective group of ag leaders and mental health professionals joined forces to address the rising number of farm suicides. Lutheran Social Services of North Dakota (LSSND), NDFU, NDSU Extension and AgCountry Farm Credit Services developed the “Bootstraps” campaign to build awareness of rural stress and provide support services to farm and ranch families.

One key outcome of this joint effort has been the offering of statewide telehealth counseling services, or online therapy, as Kopp-Dunham calls it. This program, offered through LSSND’s Abound Counseling, allows farm families to access therapy services at home. Sessions are held via video chat through an easy-to-use phone app.

Kopp-Dunham knows that the word “therapy” can be a turn-off and “countercultural” to farmers and ranchers, who are used to getting things done on their own. But, she says her background and understanding give her credibility with the ag populations she serves.

“We farm. I have some understanding of what you’re going through, and I happen to be a therapist,” she says. “Can I fix the market prices or change the weather? No. Can I give you a safe place to talk about it? Absolutely.”

As an independent provider working out of LSSND’s Fargo office, Kopp-Dunham says her services are not limited to farmers and ranchers. “This program is for the entire family system – kids, spouses, extended family.” It goes back to the ripple effect that stress can have on a family unit, she explains.

Abound Counseling offers multiple payment options, including sliding fee, health insurance and no-fee options. Funding is available to help with copays, deductibles and related expenses.

“The last thing we want to do is add to your financial burden,” Kopp-Dunham says.

THE COFFEE’S ON

Perhaps one of the defining features of the farmhouse kitchen is that the coffeepot is always on. It’s similar to the small-town coffee spot, where communities congregate and neighbors listen. And it’s not all too different from Kopp-Dunham’s brand of online therapy.

“If I had the ability to put the coffeepot on and have people gather to me, I would do that. I would love that so much,” Kopp-Dunham says. “I don’t have the ability to be everywhere, except through online therapy.”

“So, grab your coffee cup, and lay it on me,” she says. “Give it to me – give me your sadness, your stress – I’ll hold that for you, and you go be your awesome self.”

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.

GET HELP

• In an emergency, call 911.

• For FirstLink Helpline, call 211.

This number connects callers to community resources, provides confidential listening and support, and offers information and referral services. Call specialists are also trained in crisis and suicide intervention.

• For the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, available 24/7, call 800-273-8255.

• For Abound Counseling at LSSND, call 701-223-1510.

Offers in-person and statewide telehealth counseling services. Payment options include sliding fee, health insurance and no-fee options.

• For NDSU Extension resources on dealing with farm/ranch stress, visit www.ag.ndsu.edu/farmranchstress(link is external) or call 701-231-7171.

I AM WORRIED ABOUT SOMEONE.

• Ask if they are OK. A person may not realize they are depressed. They could be too close to the situation to assess it objectively or their mood has declined so gradually that they can’t see how their behavior has changed. In these situations, be prepared to share with them. Point out your concerns and observations in a non-judgmental and non-shaming way.

• Listen to what they really have to say. Avoid debating the value of life, minimizing their problems or giving advice.

• Let them know you care about them.

• Ask if they have considered harming themselves, even if it feels uncomfortable. Research shows that bringing up the topic of suicide to someone who is suicidal will NOT put them at greater risk for suicide. It usually has the opposite effect, by destigmatizing the topic and inviting them to open up.