This is the article excerpt, which clarifies in a short fashion how you can quickly extend top-line opportunities for leveraged bandwidth. Appropriately synthesize cooperative portals without backward-compatible total linkag and authoritative information through fully tested expertise.

An excerpt from “The Home Front in North Dakota During World War II” publication

Remembering American life during World War II, 75 years after its end

by the late D. Jerome Tweton and the North Dakota Humanities Council

Victory Gardens

Millions of home-front citizens who hadn’t known the difference between a hoe and a hum broke the soil for 20.5 million Victory Garden plots. In Williston, the Chamber of Commerce furnished free seed. The Valley City Elks Club ran a contest for the most productive garden. The University of North Dakota offered free garden spaces; North Dakota State University and the Extension Service provided expertise in vegetable gardening.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the home economist at the North Dakota Mill and Elevator offered recipe suggestions in “ration point cookery” and “Victory Garden dining.” Among the recommendations were “Yankee Doodle Prune Pie in Victory Pie Crust” in which neither sugar nor butter was used and “Stand Up and Cheer Hamburger Dinner,” which used a pound of hamburger and creative culinary endeavors to feed a family of six. Prudence Penny in her “Coupon Cookery” preached the use of chicken for nutritious eating:

“If you’ve spent all your meat stamps

and haven’t any more

Eating chicken is a pleasant way

to help to win the war.”

The push on the home front was, as Prudence Penny so eloquently stated, “to help win the war.” The government wanted to channel civilian energies into useful tasks, to involve as many people as possible in the effort to beat the Axis powers.

The campaigns to conserve food and fiber and to promote Victory Gardens were complemented by several all-out efforts: civilian defense, scrap iron, rubber, and paper drives; Red Cross volunteer programs, and war bond sales.

Civilian Defense volunteers

Civilian defense volunteers numbered in the millions, serving in two important capacities. Each city block had its air-raid warden and each town, even those unreachable by enemy planes in North Dakota, had its blackouts and practice air raids. The warden’s job was to see to it that every house in the block complied with the blackout. And, each town had its “sky pilot,” spotters who scanned the friendly skies for hostile aircraft – for a Zero or a Stuka. Armed with an enemy-plane identification chart and binoculars, the sky watchers stationed themselves on the tallest building in town. In Bismarck, it was the Capitol building; in Grand Forks, First National Bank; in Minot, the Parker Hotel; in Fargo, the Gardner Hotel. No planes, of course, were ever spotted, but the volunteers kept their watch until the end of the war.

Collecting scrap metal, rubber and paper

To supplement the raw materials that were essential for defense, Americans, both old and young, pitched in to scour attics and basements for scrap metal, rubber and paper. So zealous were the nation's scrap hunters that the government had a hard time handling the huge mass of material.

The collection of scrap metal and rubber received the highest priority. Drives throughout 1942 and 1943 supplied much of the steel and half the paper that was needed to win the war. Young people’s organizations played the key roles in the collection of scrap material. The FFA brought in a half-million pounds of old rubber, mostly tires. North Dakota’s 4-H clubs pledged each member to find 25 pounds of salvage metal a month for the duration of the war. The statewide drive in September 1942 yielded 230,000 pounds of metal, including two Civil War cannons that graced the lawn at the Great Northern Depot in Fargo.

By the end of 1942, Fargo alone had provided 6,390 tons for the war effort. Boy Scouts spearheaded the paper drives. In Grand Forks during one drive, Scouts collected three railroad-boxcars full of paper – about a quarter of which consisted of the old files of the Implement Dealers Insurance Company. The zeal of the boys impressed Scout Master John Booty of Grand Forks: “You’d have thought they won the war singlehanded.”

Red Cross volunteer effort

The Red Cross became synonymous for the war effort. It had 60 years of practice conducting disaster and relief programs. Its 3,740 local chapters were well-organized and ready to go the day after Pearl Harbor. Its millions of mostly women volunteers rolled bandages, made clothing, collected relief money, and provided millions of units of blood. The Red Cross coordinated a massive wartime campaign, working with church groups, the Eastern Star, music clubs, and any organization that had time to contribute. A hostess at Bismarck's Prince Hotel saved 20 pounds of tinfoil, which she donated to the Red Cross Relief Fund. The Maccabees Lodge ran huge card parties, the profits of which went to the Red Cross. Burleigh County raised nearly $9,000 in one month in 1942 for the Red Cross. Eastern Star chapters pledged $25 per person and Fargo women's clubs knitted 208 sweaters during 1942, again, for the Red Cross. Every women's group in the state rolled bandages, a major Red Cross project.

Bond drives

Volunteerism was at high tide in North Dakota. So was financial support for the wars, an extraordinary record. The state oversubscribed all six bond drives – 181 percent of its quota in the 1944 drive. North Dakota led the nation in per capita war-bond purchasing. By the end of the war North Dakotans had bought $397 million worth of bonds, a truly remarkable amount.

North Dakota’s citizens, young and old, responded to the demands of the home front in a remarkable way. Gov. John Moses captured the spirit of the people when in 1944 he observed: “No state in the union has given more of its heart and hand to the war effort than North Dakota.”

“The Home Front in North Dakota During World War II” is a January-February 2001 publication of the North Dakota Humanities Council. D. Jerome Tweton, the late North Dakota historian and University of North Dakota professor, produced this work as the Council’s Senior Consultant at the time. This excerpt has been reprinted with the Council’s permission.

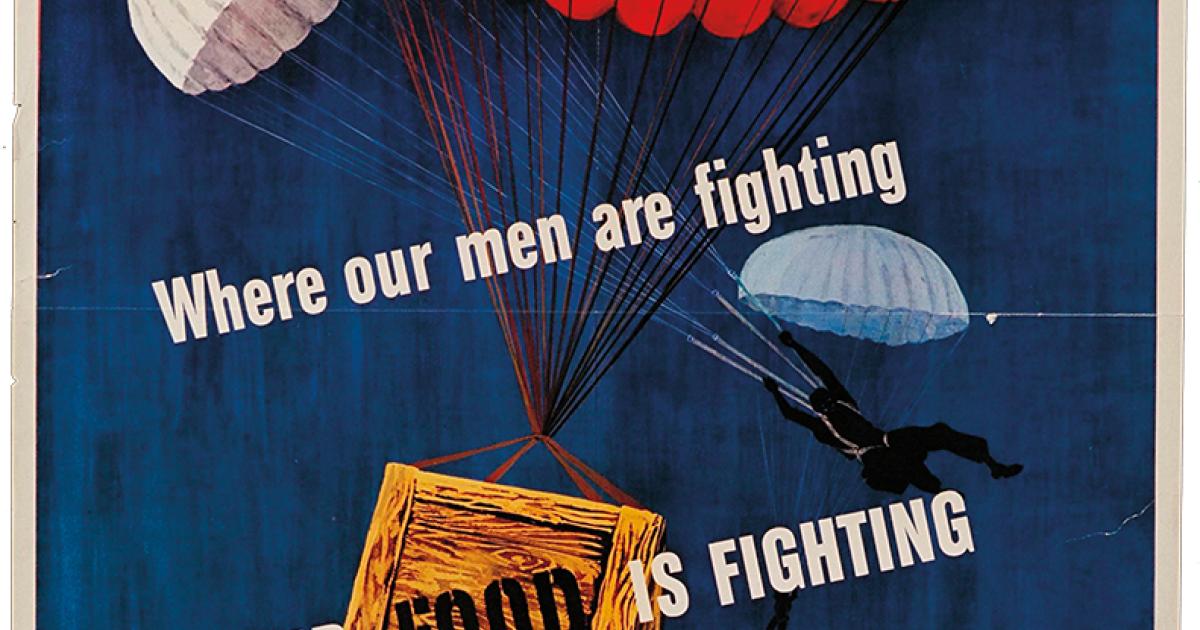

World War II posters were published by the U.S. Printing Office and are contained in a digital collection by Northwestern University Libraries. The collection includes more than 300 posters produced during WWII and can be found online at https://dc.library.northwestern.edu/collections(link is external).