The debate had already been going for at least a decade, when I produced a half-hour television show, titled “The Spring Wheat Debate,” in November 1981.

The debate was over spring wheat yield versus quality.

For decades, public plant breeders (land-grant universities) had developed spring wheat varieties that emphasized quality. That was, they argued, our selling point. It was what set spring wheat apart from other classes of wheat. In selecting for high-quality varieties, the plant breeders rejected those that were higher yielding, but of lower quality.

Farmers weren’t always pleased about that. Eventually, private companies started developing and releasing spring wheat varieties that were higher yielding, but lacking some of the end-use qualities of public varieties.

I thought about all that as I read a recent article about the National Wheat Yield Contest. It’s been going on for eight years. Farmers in two dozen states, including North Dakota, take part by selecting and harvesting their best five acres.

Anne Osborn, who is with the National Wheat Foundation and oversees the contest, told me with today’s genetics, you can have both yield and quality. And while yield is the primary focus of the contest, she says there is a quality component as well.

Since 1981, spring wheat acreage in North Dakota has declined from 7 million acres to 5.4 million. Meanwhile, acreage of corn has increased more than fivefold, and soybean acreage has gone from 200,000 to more than 5 million, surpassing spring wheat.

While spring wheat may never regain the prominence it once had, the yield contest could play a role in spring wheat’s future.

Some wheat industry leaders, concerned about preserving hard red spring wheat’s reputation for high quality, worry farmers will emulate the contest winner, who got bin-busting yields of lower quality spring wheat. But others argue if enough farmers learn you can get exceptional yields of good quality spring wheat, then spring wheat might at least remain competitive as a viable option in growers’ cropping systems.

And so, the debate continues.

___

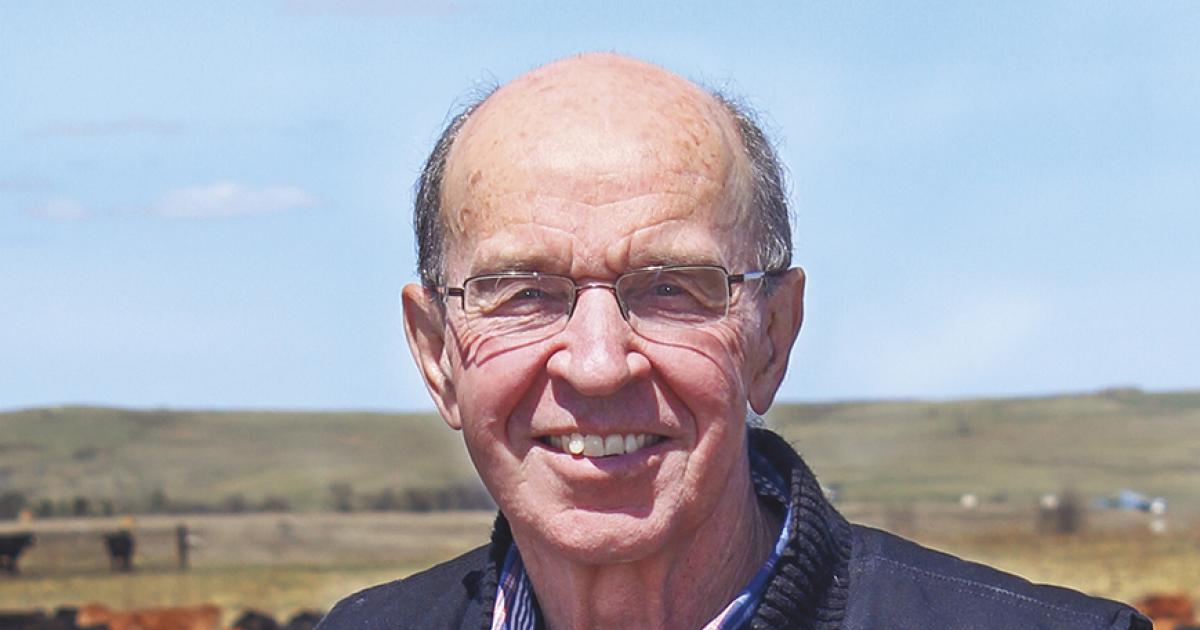

Al Gustin is a retired farm broadcaster, active rancher and a member of Mor-Gran-Sou Electric Cooperative.