“In the early 1800s, a scientist in England named Michael Faraday noticed that when he rotated a metal disc through the middle of a horseshoe-shaped magnet, he could get electrons to flow together in an electric current. Engineers soon took over and made Faraday’s process really complicated. And really useful. Today, nearly all our electricity comes from turbines that spin a magnet inside a coil of wires.”

We depend on electricity 24/7, but have you ever wondered how it’s made, or where it comes from?

To understand the basics of something so important to modern life, think about steam from a teakettle and those magnets stuck to your refrigerator door.

Magnetic metals in nature attract each other because parts of the atoms that make up the those metals want to match up with others. Those restless atomic particles are called electrons—and that’s where we get the word “electricity.”

In the early 1800s, a scientist in England named Michael Faraday noticed that when he rotated a metal disc through the middle of a horseshoe-shaped magnet, he could get electrons to flow together in an electric current.

Engineers soon took over and made Faraday’s process really complicated. And really useful. Today, nearly all our electricity comes from turbines that spin a magnet inside a coil of wires.

One way to turn those turbines is by heating liquid into steam that forces the turbine to spin, using the same principle that makes a teakettle sing. When you boil water on your stove, that liquid expands more than 1,000 times as it vaporizes. If you’ve ever had your hand burned near boiling water, you’ve felt the power that steam produces.

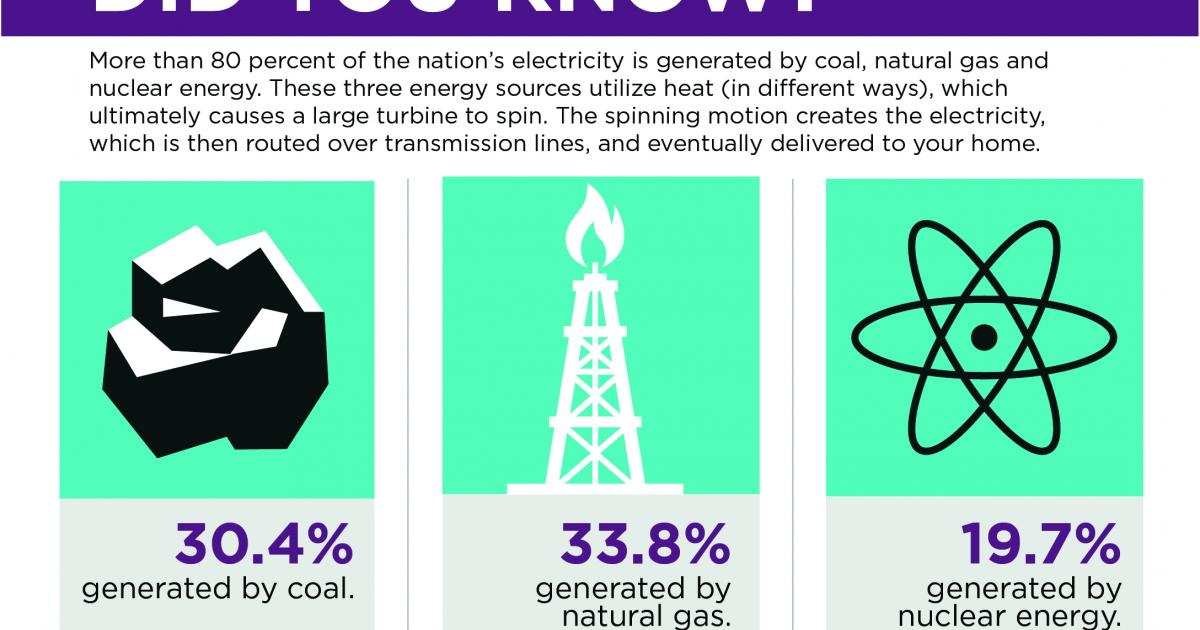

The use of heat to spin a turbine generates more than 80 percent of our electricity using either coal, natural gas or nuclear power.

Coal

Coal is dug from the ground, either near the surface, or from deep underground mines, then is shipped to power plants, often by train.

At the power plant site, the coal is stored in large piles on the ground until it is ready to be burned. The coal chunks are crushed into smaller pieces, or even a powder, that is burned in a furnace.

The heat from that combustion is used to turn liquid into the steam in a furnace/boiler that spins the steam turbine/generator producing electricity.

Large transformers at the plant boost the voltage of the electricity (while lowering the current and minimizing line loss potential) for shipment across the country through tall transmission lines. As it gets closer to where it will be used, a substation of transformers reduces the voltage to a level that can be safely delivered to a smaller transformer on the utility pole or pad mounted transformer in your yard, decreasing the voltage further for use in your home.

As simple as that process sounds, each step is extremely complicated in order to make it as efficient and safe as possible. The furnace burns the coal up to 3,000 degrees, and the steam it produces gets hotter than 1,000 degrees. Coal contains elements that get captured and removed through sophisticated pollution controls. That environmental equipment can cost as much as the power plant itself.

Coal plants produce about a third of the nation’s electricity.

Natural gas

Ancient plants and animals that died long ago turned into coal, oil and natural gas—that’s why all three are called fossil fuels.

Like coal, natural gas comes from the ground, and it can burn in a way that can drive a steam turbine or a natural gas-fired combustion turbine. Unlike coal, you can’t hold it in your hand—it’s a colorless gas, like air, and has to be transported by pipeline. Natural gas can also be piped directly into homes where it can be burned in water heaters and stoves.

In a natural gas power plant, specially designed combustion turbines burn the gas to make them spin, generating the electricity. The way natural gas turbines work is similar to a jet engine, and in fact they are a large, complicated version of what you see hanging on airplane wings.

Natural gas electric generation has advantages over coal: The plants are simpler, cheaper to build, require less staff and they can be shut down and powered up more quickly. Natural gas doesn’t contain as many pollutants as coal, so fewer environmental controls are needed. Natural gas burning also produces less greenhouse gas. In the past, natural gas was more expensive than coal—until the 1990s when fracking and other new drilling techniques flooded the market. Natural gas prices dropped dramatically and many utilities are using it to replace coal generation.

Natural gas plants now produce about a third of the nation’s electricity, about the same as coal.

Nuclear

A nuclear power plant works basically the same as a coal plant—making steam to spin a turbine and generator.

The difference is that instead of burning coal, heat from a nuclear reactor heats the liquid into steam.

The basic fuel for a nuclear power plant is uranium, which is mined from the ground. It must then be formulated into expensive and complex fuel components for utility use.

A little uranium can last a long time, making it a promising, inexpensive power source, producing no atmospheric emissions, as happens with combustion of coal or natural gas. But the concentrated radioactivity in the nuclear reactor is potentially so dangerous that complex, expensive safety measures need to be part of any nuclear plant. Highly technical control systems need to be in place to slow or shut down the level of heat produced, and the nuclear reactor needs to be inside a strong containment building to keep radioactivity out of the atmosphere in the event of a low-probability accident in the reactor core.

Another controversy still has not been solved – how to dispose of the spent nuclear fuel, which can stay radioactive for millions of years before the radioactivity is brought down to naturally occurring radioactivity in the environment. Most of the spent fuel is currently stored in pools of water and dry storage casks at the site of the nuclear plant.

Nuclear power generates about one-fifth of the nation’s electricity.

Heat produced by coal, natural gas and nuclear power generates about 80 percent of our electricity. The rest comes mainly from hydroelectricity, solar and wind.

Paul Wesslund writes on cooperative issues for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, the Arlington, Va.-based service arm of the nation’s 900-plus consumer-owned, not-for-profit electric cooperatives.