Preparing students for future tech careers, AI in the workplace

Bismarck State College students Adrianna Aguayo and Cole Edwardson use a robotic arm in the West Flex Lab at the Advanced Technology Center on campus. Both students are peer mentors and work with BSC’s XR for VR project, which uses immersive technology to connect North Dakotans with disabilities to high-wage manufacturing careers.

From the oil pumped in western North Dakota to the light switch flicked on and off many times a day, technology is interwoven into society.

When the coordinator of the writing program at the University of North Dakota (UND), Anna Marie Kinney, goes to buy a hardcover book from the store – seemingly un-technological – she drives her car with her phone’s GPS. Once there, she pays with a credit card.

“We live in a tech-mediated world. And so, by extension, our (career) fields also exist in that world. I think (career fields) have benefited from (technology), and they have lost things because of it, and our identity is constantly shifting,” Kinney says.

In a technological world, how are North Dakota institutions of higher education preparing students for careers in technology? After all, doesn’t every career now require technological literacy?

ON-CAMPUS TECH LEARNING

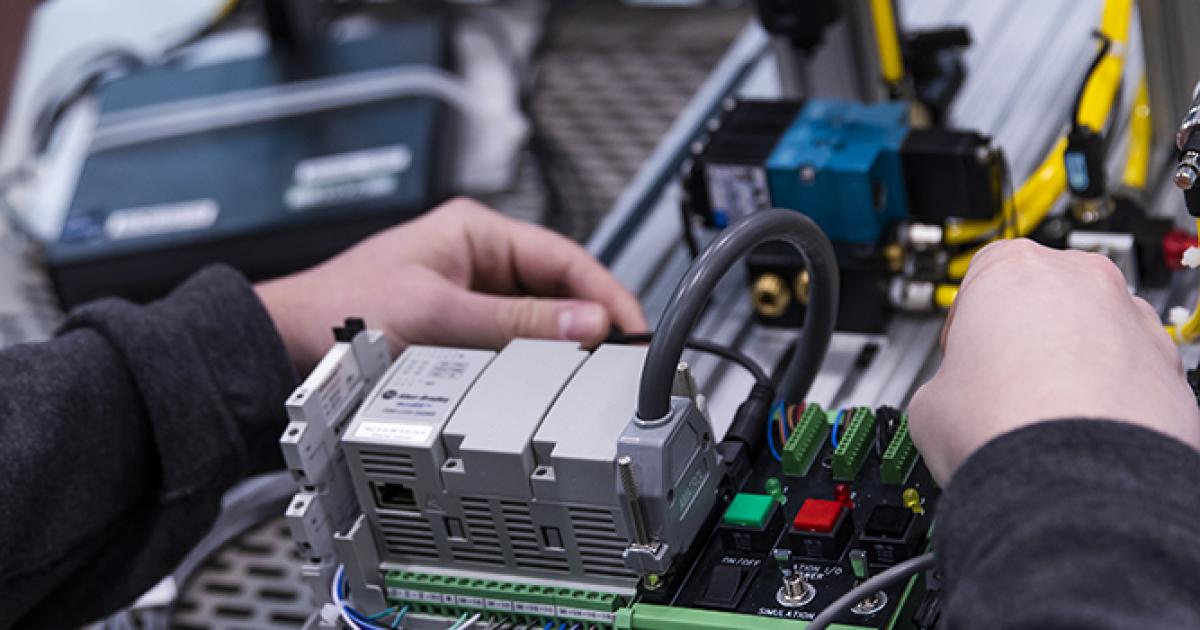

At Bismarck State College (BSC), North Dakota’s polytechnic institution, technology has always been a priority. The college offers a multitude of programs, including cybersecurity, mechatronics engineering technology, lineworker training and more. Inside BSC’s new Advanced Technology Center, two 10,000-square-foot flex labs allow hands-on learning for students in mechatronics, robotics, automation and engineering technology. The labs have rows and rows of technology, including 3D printers and robots students have named “Rosie” and “Dot.”

“We have a great amount of technology in our West Flex Lab, which provides many opportunities for hands-on learning, so we can ensure our students are mastering these skills before they leave us and transition into the workforce,” says Mandi Eberle, BSC assistant dean of automation, energy and advanced technologies.

It is imperative for colleges to prepare students for careers in technology, says Mari Volk, BSC dean of current and emerging technologies.

“Without those skilled laborers going out into our workforce, we don’t have vehicles to drive. Cheerios aren’t on the shelf in the grocery store. There’s no one to fix your vehicles. We don’t have electricity without the folks that are going through these programs. These are the careers that keep our world moving,” she says.

At North Dakota State College of Science (NDSCS) in Wahpeton, the focus is giving students hands-on tech learning pertinent to their career, while working closely with industries in North Dakota. This collaboration connects students to future employers and helps the college tailor its curriculum to produce a career-ready workforce.

NDSCS Dean of Career and Technical Education Kyle Armitage sees how tech education goes beyond traditional tech careers in cybersecurity or computer science, crossing into agriculture, health care, construction and other fields. At NDSCS, technology is used in the classroom through simulated health care environments, unmanned aerial systems, drones, GPS data sensors for farmers and technology that aids student learning in all fields.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

In recent years, colleges have adapted to artificial intelligence (AI).

BSC was an early adopter of AI and quick to develop AI programs, Volk says. Currently, BSC offers a certificate, associate degree and bachelor’s degree in AI, but new and emerging technologies are explored in programs across campus. Professors in everything from English to nursing have made a point to learn about AI and teach students about it.

BSC is not the only college in North Dakota prepping students for a world with AI.

Minot State University (MSU) also prepares students for tech careers with degrees, certificates and classes in computer science, cyber defense and now general courses in AI.

Darren Seifert, assistant professor of computer science and chair of the math, data and technology department, has seen how the college has adapted to the changing technology, which has “exploded” in the last five years, he says.

Last fall, MSU began offering general education courses in AI, focusing on daily application and functionality. Several fields now require competency in AI for graduates entering the workforce.

“They are expected to understand how to use AI within their discipline,” Seifert says. “We see that as a driving factor. Companies are looking for people that have these skills. That is why it’s so important to evolve the programs and specialize. We need to take our courses and our programs where employers are looking for graduates.”

Valley City State University (VCSU) introduced the AI Institute for Teaching and Learning in 2025, outlining the university’s commitment to include AI in the curriculum and plans to offer comprehensive training programs for K-12 teachers in AI.

Already, AI is seen in classrooms across the VCSU campus as not only a tool for education, but a technology requiring literacy. One professor is even using AI in art classes.

“It’s pretty apparent if you watch what’s being written about in the news across the globe, AI is taking a hold in all facets of business work,” says Jerry Rostad, VCSU director of special projects.

A FUTURE YET TO BE DEFINED

AI has brought both optimism and pessimism for the future.

Concerns of the environmental costs of water and electricity use, lack of critical thinking and subsequent decline of critical thinking skills, and AI’s ability to “hallucinate” incorrect information exist. While colleges and universities integrate AI into curriculum, they must also consider these ethical questions.

At UND, an “AI collective” of faculty and professors has been formed to bring AI to the university, while simultaneously addressing AI concerns.

Like many people, Richard Neal Van Eck, who co-chairs the AI collective and is associate dean for teaching and learning at the UND medical school, was skeptical of AI at first.

“The more we looked into it, the more we realized, ‘No, this is something that can fundamentally change everything,’” he says.

Van Eck’s focus is how to teach more effectively with AI tools and AI applications in health care. Seeing what this technology has done in health care has led him to believe there is a “moral obligation” for its use in the medical space.

According to Van Eck, a hospital on the East Coast has successfully used AI to predict if a specific cancer will progress. While people were doing this with 56% accuracy, AI does it with 80%.

“So, now you are talking about solving a problem that is literally life and death for some people,” he says. “We have to use it. We are morally obligated to. It literally saves lives. So, then the question becomes, how do we use it? What are the right ways to use it? What are the wrong ways to use it?”

Teaching students how to both use AI correctly and understand the ethical concerns is important, Van Eck says, so they make informed decisions on its use. When used correctly, Van Eck believes AI will enable the future workforce to do work faster and better.

“They are afraid that AI is going to replace teachers… And the answer is no, AI will not replace teachers, but teachers who use AI will replace teachers who do not,” Van Eck says.

Kinney, who co-chairs UND’s AI collective with Van Eck, suggests teaching students about AI isn’t necessarily about AI at all. Rather, it’s about providing students a higher education that prepares them for a future not yet here.

“Now, we are watching that future come at a much quicker pace, right? And it changes dynamically. So, we have always had a responsibility to support learning in students that is transferable, that is skill-based, and that helps create a nimble and adaptable workforce. That is our mission. It always has been,” Kinney says.

Van Eck says AI is not going to destroy the world, nor will it save it.

But it will be up to future generations to decide, Kinney says.

“The future of tech is vibrant, and it is strong. And it is in some ways yet to be defined – and will continue to be defined by the students we have in these classrooms right now,” she says.

___

Kennedy DeLap writes and photographs for North Dakota Living. She can be reached at kdelap@ndarec.com.