Community honors pilot’s ultimate sacrifice

During a memorial dedication to a fallen soldier, the Schafer-Boye-Lange American Legion Post 69 from Flasher sounded a 21-gun salute and played taps. Photos by Bert Richardson

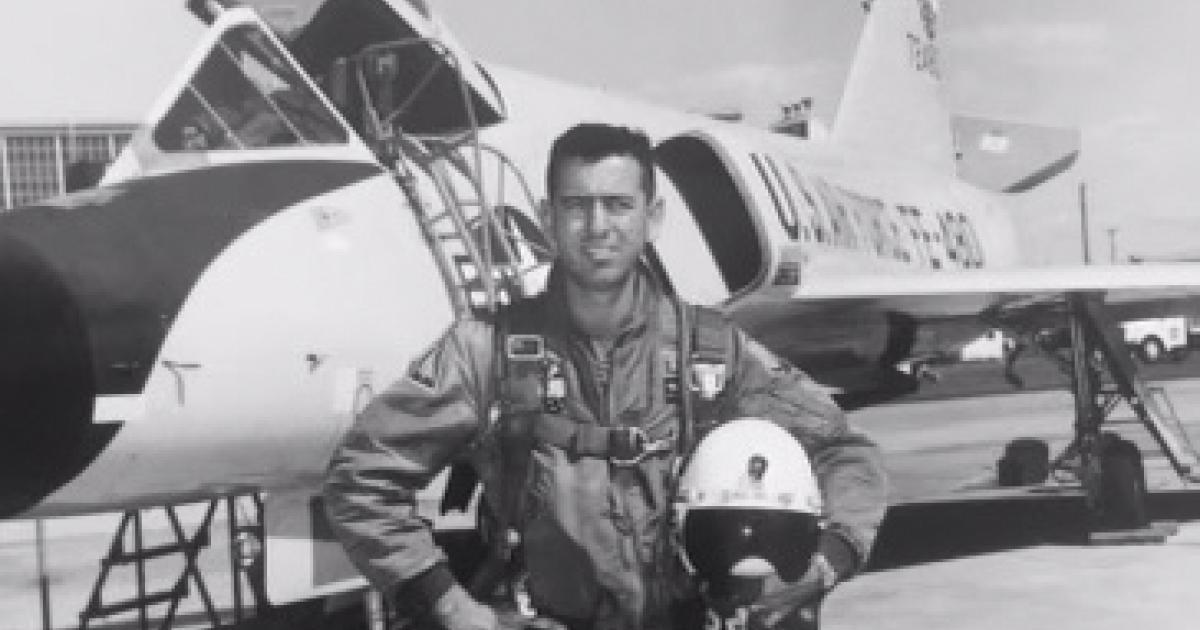

More than 60 years after Capt. William Richardson’s F-106 aircraft crashed into the frozen prairie near Flasher in 1963, a memorial saluting his sacrifice now stands alongside Highway 31 in Grant County.

Richardson’s daughter, who was 2 years old when her father died, tearfully attended the memorial’s dedication, as a 21-gun salute sounded into the pristine sky and a P-51 Mustang roared overhead in a flyover.

The soldier’s ultimate sacrifice has been honored in a warm embrace by the state, even though he was not a native son.

When duty calls

Born in Mississippi in 1930, Richardson joined the U.S. Air Force in 1950, eventually stationed at the Minot Air Force Base flying the F-106 Delta Dart, an interceptor aircraft used through much of the Cold War era.

At the Minot Air Force Base, home to the 5th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, the F-106’s specific mission was to intercept the Tupolev Tu-95, a Soviet Union long-range strategic bomber.

In the midst of the Cold War era and a North Dakota winter hovering below 0 degrees, Richardson was among a group of six pilots who took off from the base to practice interceptions on Dec. 19, 1963.

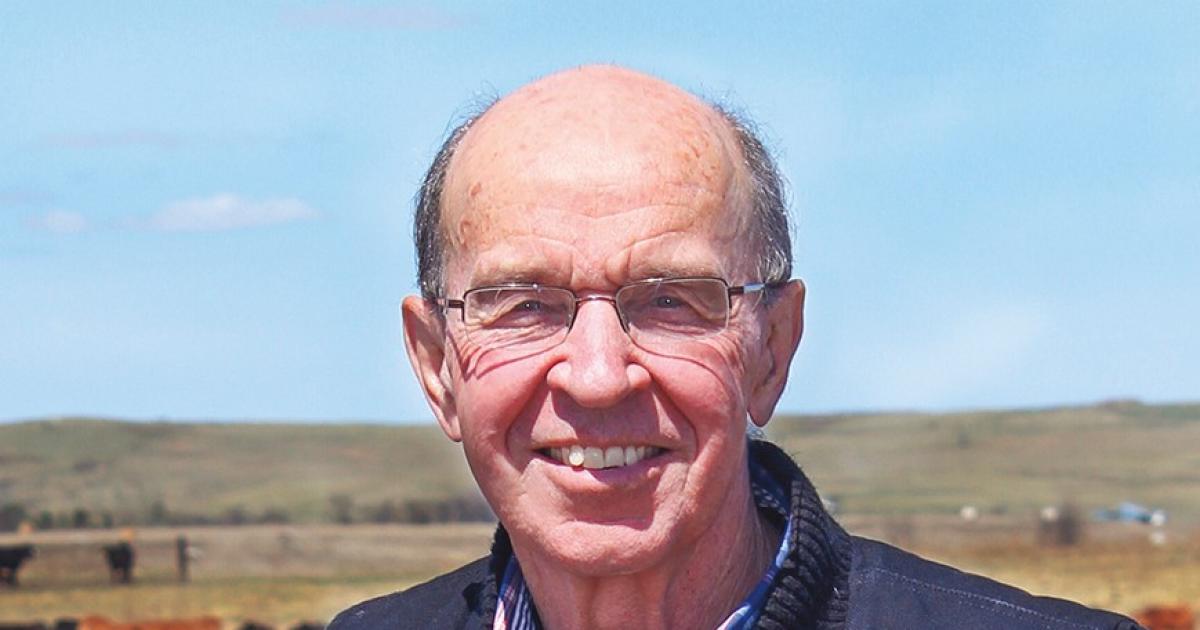

Scott Nelson, a Flasher area rancher, shared the story from that fateful flight in a 2021 Dakota Datebook article.

Richardson and two other pilots were flying at 24,000 feet southwest of Bismarck, when Richardson’s plane made an abrupt breakaway from the other aircraft, Nelson wrote.

Radar contact with Richardson’s plane was lost at 10:18 a.m., when it plummeted into a frozen field between Flasher and Raleigh, disintegrating on impact. Richardson was 33 years old when he died in the fiery crash.

His death was directly attributed to the failure of the ejector seat, meaning Richardson wasn’t able to parachute from his stricken aircraft. The incident resulted in the entire squadron being grounded, Nelson wrote.

The news of the pilot’s death arrived at the doorstep of the Richardson home on the base while his wife and daughters, 13 months old and 2 years old, were preparing for the holiday. Richardson’s commander, Col. Jacksel Broughton, carried the news himself.

“She was baking Christmas cookies with her two little girls beside her and he had to break the news to her,” Nelson says, his voice breaking with emotion.

Nelson, who served in the North Dakota National Guard, often pens aviation-related articles for Dakota Datebook as an aviation history buff. He has interviewed veteran aviators and painted scenes from their escapades. His original 16 historic paintings, along with the veterans’ stories, are displayed in the Scott Nelson Gallery at the Dakota Territory Air Museum in Minot.

Similarly, the memorial and the dedication event in July were a community effort to keep Richardson’s service in the forefront, Nelson says.

“This is so we remember,” Nelson says. “You don’t want to forget history.”

During the memorial dedication July 19, the Schafer-Boye-Lange American Legion Post 69 from Flasher sounded a 21-gun salute and played taps. The Flasher and Carson American Legions funded the memorial. A plaque in honor of Richardson is accompanied by a cutout of a fighter plane, created by students at Flasher High School. The memorial, located about 3.5 miles south of Highway 21 on Highway 31, is near the crash site.

“It’s the whole community. I couldn’t have done it without all this help, and I was just the one who suggested it. Everybody else took it and ran with it,” Nelson says. “Just look at how many people showed up out there that cared about him.”

A healing journey

“I do know my dad loved what he did,” says Richardson’s daughter, Trish Healy, who traveled from Atlanta, Ga., to attend the memorial dedication.

“I appreciate everyone in this area. It’s like one of their own has passed away,” Healy says. “It’s amazing to me how they have honored my dad all these years later.”

As she speaks, Healy touches a pendant containing a bent and aged 50-cent piece from the crash site, most likely from her father’s pocket.

On May 14, 2020, retired Master Sgt. Robert Haring, living in New York, emailed the Minot Daily News, seeking help in locating a Richardson family member, the Minot Daily News reports. Haring worked as a crew chief on the F-106 aircraft at the Minot Air Force Base and was at the scene during the crash investigation.

He sent the coin to Healy 57 years later, along with his journal entries from that day.

Because of the heartbreak, the crash was rarely discussed within the Richardson family, Healy says.

“My mom didn’t speak a lot of it. Obviously, it was very traumatic for her,” Healy says. “It broke her heart.”

Healy was 43 years old before she really started unraveling what happened to her father.

“My journey started 20 years ago, when we found out in a very strange, divinely inspired way that there was a building on the Minot Air Force Base named after my dad that no one in my family knew about,” she says.

A dormitory at the Minot Air Force Base was named Richardson Hall in 1967 to honor the pilot’s sacrifice, but the family did not learn of its existence until 2004. A rededication of the building in 2005 was attended by Richardson’s wife, two daughters and other family members.

Richardson’s nephew discovered the existence of the building when an airman he knew was stationed in Minot and sent a large envelope of information, including a mention of Richardson Hall.

“For the first time in my life, I think I really grieved,” Healy says.

“It started out as a grieving journey and now it’s really been a journey of healing,” Healy says. “It’s very emotional.”

The late Victor Ternes, who owned the land of the crash site, was one of the first people on the scene. The Ternes family took Healy to the site last summer.

Local residents describe witnessing the crash, hearing a loud whistle and seeing a ball of fire and smoke overhead while feeding cattle. Another saw a fireball when the plane struck the ground.

Over the years, local residents recovered pieces of the plane at the crash site and tucked them away in drawers and boxes. When Healy came to the memorial dedication, several of those pieces were solemnly handed to her by local residents, including a piece Nelson’s father found at the site.

“To see the actual pieces of the airplane, I wasn’t expecting that, so that was pretty emotional for me, too,” Healy says.

Other lives saved

While some type of malfunction on the plane itself caused a fire and the plane crash, the ejection seat failure caused Richardson’s death.

“My dad was the 13th pilot to die in an F-106 because the ejection seat didn’t work,” Healy says.

Broughton, who commanded the 5th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron at the Minot Air Force Base in the 1960s, was instrumental in getting the aircraft’s deadly ejection seat replaced. He wrote about it in his book, “Rupert Red Two: A Fighter Pilot’s Life from Thunderbolts to Thunderchiefs.”

The book describes his decision to ground his squadron of F-106 Delta Dart fighters after their ejection seats proved lethally dangerous to pilots, which brought him into conflict with his superiors.

“It could have ended his career,” Nelson says.

But after Richardson’s crash, Broughton won the battle on the ground, as the plane was grounded until the ejection system was reconfigured.

“The seat was a killer. It took a career-threatening campaign against industry and higher headquarters, but we finally replaced the killer seats for the entire 106 fleet. When the last 106 retired two decades later, the new seat had a 100% success rate within parameters,” Broughton wrote in a 2012 article, two years before he died at the age of 89.

Richardson’s death led to saving other lives.

“The ultimate outcome was the installation of a new ejection seat that used a rocket catapult instead of a ballistic charge. The new system became standard for the F-106, and it saved many pilots in the following years,” Nelson wrote in Dakota Datebook.

Representing the Minot Air Force Base, Capt. Levi Hilgenhold, a B-52 instructor pilot and 5th Operations Group executive officer at the base, also attended the memorial dedication.

He is uniquely familiar with the sacrifice of soldiers.

“It’s something that I’ve experienced in my time. There are two very close friends of mine that perished in training accidents. That sacrifice and service doesn’t change over the decades. It really is timeless in that regard,” he says.

And on a patch of North Dakota prairie, Richardson’s service and sacrifice will be remembered for all time.

“The greatest takeaway from this is that the community came together through a grassroots effort to dedicate this memorial,” Hilgenhold says.

“I’m just blown away by how all these years later, there are people that still honor my dad’s sacrifice,” Healy says. “For me to be here today, it brings me closure in a lot of ways, although I don’t know if that’s a hole that ever gets closed, but it helps fill that hole with good memories.”

___

Luann Dart is a freelance writer and editor who lives in the Elgin area.