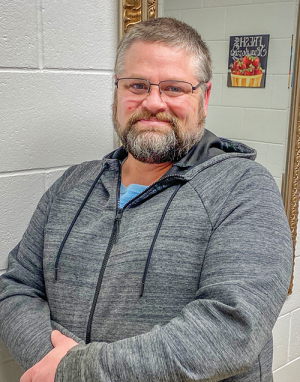

Greg Palmer fidgets with his eyeglasses on the table in front of him, his eyes momentarily brimming with tears, while his wife’s hand reassuringly rests on his wrist.

Thoughts tumble from him like leaves whirled by the wind, as he poignantly reveals his personal journey of opioid addiction – and recovery – in a story that started 16 years ago.

A shoulder injury, a car accident and other pain propelled Palmer to opioids, but he felt he was using the pain medications responsibly – at first. Then the siren call began.

“I found myself using my pain medicine more than I had. I had always been really responsible with it. I’ve been on this pain medicine for 16 years,” he says. He found himself depleting a prescription early or doubling the dose.

“I didn’t think there was a problem with it, other than I knew I shouldn’t be doing that,” he shares.

Palmer soon realized he was addicted.

“The life you are living is not your life. You’re a slave to that medicine. Everything you do revolves around it,” he says.

Becoming a statistic

Throbbing pain, silenced by prescription painkillers. Then another pain occurs – addiction. And another silence – an unwillingness to come forward for help until it’s too late.

Every day, 128 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

“The misuse of and addiction to opioids – including prescription pain relievers, heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl – is a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare,” according to the NIDA.

“The statistics regarding opioid abuse are staggering, and our local communities are not immune to this nationwide epidemic,” says Elgin’s Jacobson Memorial Hospital Care Center (JMHCC) CEO Theo Stoller.

Roughly 21-29 percent of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, the NIDA states. In 2017, there were 68 drug-related deaths in North Dakota. This rise from four in 2014 is concerning, according to the NIDA.

Poised to help

The Glen Ullin Family Medical Clinic and the Richardton Clinic, both operated by JMHCC, are poised to help curb this epidemic, with specially trained medical providers who can help patients withdraw from opioid use with medication-assisted treatment.

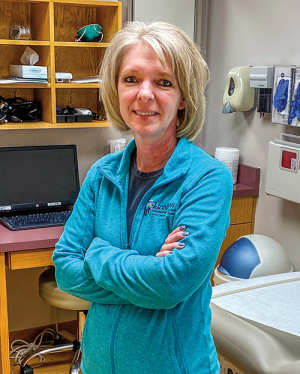

“We need to let people know we’re here. A lot of people don’t realize there’s another option,” says Rhonda Schmidt, a family nurse practitioner (FNP) at the Glen Ullin Family Medical Clinic.

The providers, including Schmidt at the Glen Ullin Family Medical Clinic, and Jolene Engelhart, an FNP at the Richardton Clinic, offer medication-assisted treatment to withdraw from opioid dependence. The providers are experienced with administering buprenorphine, or Suboxone. Coupled with a complete treatment plan, Suboxone is used in the treatment of opioid dependence.

In eastern North Dakota, Community Medical Services, Fargo, also offers medication-assisted treatment, also requiring visits with a licensed addiction counselor.

“We have a lot of people who travel a distance,” said Wendy Moore, an FNP with Community Medical Services. “Suboxone is a gold-standard treatment for opioid use disorder. Being diagnosed with opiate use disorder is a lot like being diagnosed with high blood pressure or diabetes. They just want to feel normal. Being on medication-assisted treatment normalizes their body and their brain so they’re able to get a job and a normal life.”

Dependence happens when the body physically adapts to a drug and becomes tolerant to it. This leads some people to need more of the drug to create the same effect. Addiction occurs when uncontrollable cravings cause someone to become unable to stop using a drug, even though it leads to harmful results.

And it can happen to anyone, Schmidt says.

Greg Palmer is one of those “anyones.”

A gradual spiral

Schmidt started treating Palmer three years ago for pain management prior to a third shoulder surgery.

“A lot of these patients, I feel, fall through the cracks,” Schmidt says. “If they are having pain, someone should be there to listen to them and help them. It may not always be with pain medication. There are other ways that you can help them manage their pain and maybe even decrease the use of narcotics.”

“There are so many people out there who are not able to get the care they need, so they are turning to street drugs and that is unsafe,” she shares.

Schmidt guides her patients who are misusing pain medication to the realization it is actually harming them, she says.

Just over a year ago, Palmer began that realization.

“Things got kind of rough and threw a little stress into the catalyst of life,” Palmer says. “I started finding I could use my pain medicine to just numb myself or not worry about things, so I started taking it more than I should and not the way I was supposed to, and at that point I knew, man, this isn’t right. I was using it for an escape from reality.”

Then he began using methamphetamine “every now and then” to enhance the feeling of the opioids.

Last summer, Palmer started failing random urine tests at the clinic.

“I was pretty ashamed of myself,” he says. “(Schmidt) basically looked at me and said, ‘Are you willing to admit you have a problem?’ and I said, ‘Obviously, I do.’ She has always been a constant.”

“I told myself a few times I need to get help. But I thought, I’ll be OK. I can deal with this. I was so scared to get off the pain medication,” he says. “And I thought when I get off these pain medications, how am I going to work? How am I going to get up?”

Hitting rock bottom

Scheduled for a fourth shoulder surgery in October, Palmer’s goal was to stop using the pain medications following the surgery. But an arrest fast-tracked him to seek help. By December, his wife, Carole, had left him.

“It got to the point where I didn’t recognize him at all and I didn’t realize what was going on and ultimately I left. … I didn’t know him,” Carole says.

Patients sometimes wait until they are scraping desperation before seeing a provider, Schmidt says.

“They are tired of allowing their addiction to control their life. They had hit that rock bottom place in their life where they couldn’t focus on day to day. They could just focus on when they could take that next pill and where they were going to get that next pill from,” she describes.

Greg had hit rock bottom. On Dec. 31, 2019, he entered a 30-day residential treatment facility, Heartview Foundation in Cando. Before starting Suboxone, patients must first be in withdrawal.

“That first seven days, all I wanted to do was take medicine, all I wanted to do was take a pain pill. I was in pain and I didn’t feel good and I didn’t want to be in this place,” Greg says.

But he had another epiphany during the early days of treatment.

“After day five, I realized, holy crap, I haven’t been myself for a long time, and I didn’t even know I haven’t been myself,” he describes.

Greg had been reluctant to seek treatment because of his mixed feelings about Suboxone and his ability to withdraw from opioids.

“I didn’t want the Suboxone. I didn’t want anything to do with it. I read it’s just trading one for another and it’s really hard to get off of and there’s a bad stigma,” he says. “I didn’t want to be on anything that I would love.”

But he reluctantly started the treatment.

“About the first 20 minutes after the first time I took it, boom, the withdrawals, everything, just went away and I felt like I got clarity. It took the withdrawals away, so I wasn’t sick anymore, but it didn’t give me any kind of buzz or any kind of feeling. It just made me feel like I was normal. I thought there might be something to this,” he says. “My worries went away.”

Greg describes not being himself while addicted to opioids, feeling isolated, never laughing and simply not enjoying life.

“A lot of them say they didn’t realize they weren’t themselves anymore until they were able to start treatment and now are able to be successful. They are able to go to work and be able to function and be a part of their family with the treatment,” Schmidt says.

“It’s such a gradual change,” Palmer says. “I hadn’t heard myself laugh in so long.”

“Just constantly glass half empty. Stuck in this horrible, negative spiral,” Carole describes. “I knew he was hurting, but when he first started with the constant pain medication, I knew he had pain and I would tell the kids, ‘Grumpy’s home,’ and he hated that. He was grumpy and cranky and just extremely irritable.”

Greg now takes Suboxone three times a day.

“It took away the desire to even want to take any pain medicine. I don’t even think about it. It keeps that desire or craving away,” he says. The medication also alleviates his pain.

“I think my pain is better controlled now than it was in the last six years,” he says.

“It actually treats pain better than narcotics. For the majority of my patients, once I get them off the opioids and on the Suboxone, they say their pain is way better managed on the Suboxone than it was with the opioids,” Schmidt says. “I like helping people and it’s not only about providing them with health care, but also including both their mental and spiritual health.”

A bridge to getting better

While Greg started his treatment at a facility, he now meets with Schmidt regularly to continue treatment. Patients can also start treatment as an outpatient through the clinics.

“We discuss the program in detail to make sure they are willing to follow the guidelines, because they are so strict,” Schmidt says. The treatment includes frequent visits and random drug screenings. JMHCC and its affiliated clinics in Elgin, Glen Ullin and Richardton have also implemented a pain medication agreement for patients prescribed pain medications.

The agreement provides for discontinuation of a pain medication prescription under certain conditions and requires consent for a urine drug screening to determine that medications are being taken as prescribed.

If it is determined that the patient is not abiding by the pain medication agreement, the patient will be terminated from the agreement and will no longer be prescribed pain medications.

“All of these measures are being put into place to try to decrease the abuse of opioids,” Stoller said. “We are seeing an increase in the abuse of these drugs. The abuse of pain medications can have dangerous outcomes and we hope to identify and help patients who may have an addiction to pain medications.”

Once patients start Suboxone, the treatment is often long-term, as patients typically remain on Suboxone for years.

Carole describes the medication-assisted treatment as a tool, or a bridge to getting better.

“Maybe you’ll be on it forever, maybe you’ll be on it for a few years, but does it matter?” Carole says. “It’s not going to be the thing that’s going to cure him. He still has other parts that he has to work on. … In order for him to be able to do the things that he needs to do to make himself healthy, this is allowing him to do it,” she says. Greg is attending after-care programs weekly and attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings as well.

“Those are things that are helping me learn about my addiction and helping me to stay the course,” he says.

Greg shares his story, with hopes that others will see themselves and seek help also.

“When you think everything is crumbling and falling around you and nothing’s there for you, go see Rhonda or go see a provider, because you can get that life back and you don’t need that medicine to make you feel the way that you feel,” he says.

“When you do this medical-assisted therapy, you don’t have that desire to be a slave to that drug. You can actually live and enjoy your life, and you don’t have the sickness that you are so worried about or the withdrawals that you are so worried about or the lack of motivation that you are so worried about,” he says.

“I was so tired of hiding and lying to everybody about what I was doing,” Greg says. “It’s so freeing when you don’t have to do that anymore. At the very least, if you want to feel better about yourself, get the help and at least free yourself of that lie that you’re telling everybody around you.”

“It probably saved my life. It definitely saved my marriage and my family,” he says.

Luann Dart is a freelance writer and editor who lives in the Elgin area.