On a warm evening in early August, we sat onboard the Lewis and Clark Riverboat on the Missouri River and listened as esteemed author and historian Tom Isern read from his latest book, “Pacing Dakota.” The passage Isern chose told of a homesteading family in McIntosh County and of how a prairie fire in 1898 had killed a daughter and the mother who tried to save her.

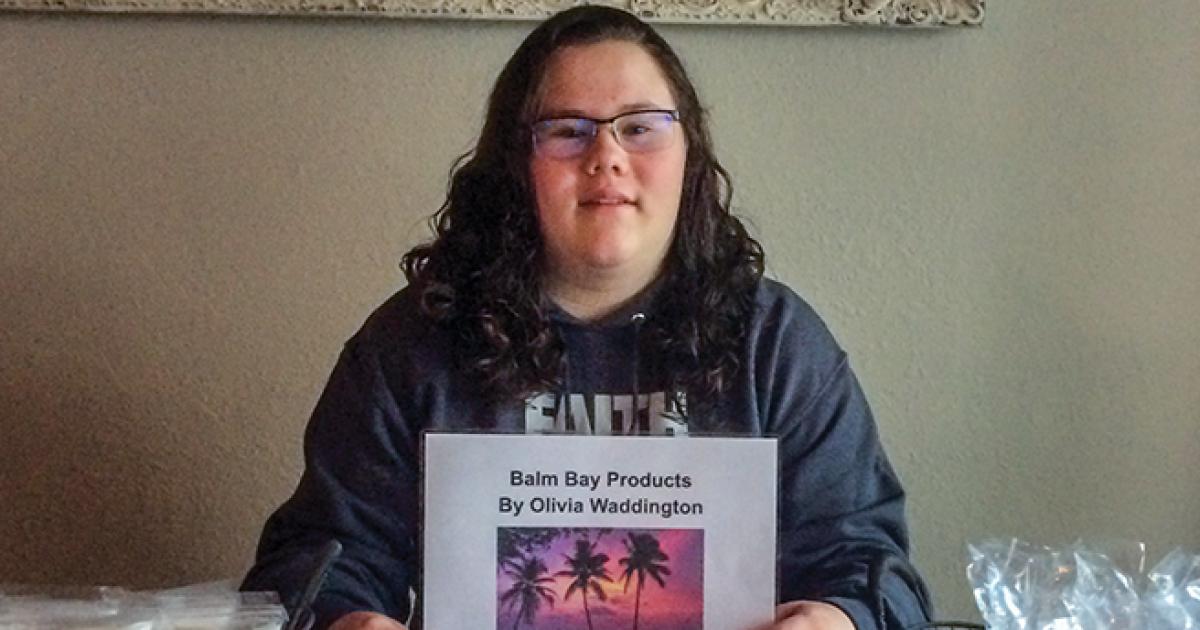

Al Gustin

I couldn’t help but think of my homesteading ancestors and how terrified they must have been by prairie fires. But I thought, too, of how fire had been an important component in the development of prairie and forest ecosystems.

I’ve written before of how range scientists are looking at fire, controlled burning, as a way of improving rangelands. Some of that work is being done at North Dakota State University’s Central Grasslands Research Extension Station near Streeter. There, grasslands specialist Kevin Sedivec says: “We brought fire into the picture to try and address (if we can) and get a better control of the exotic grasses while enhancing our broadleaf flowering plants, our native plants.”

Researchers at Streeter are doing prescribed patch burning, on a different 40-acre patch each spring. Fall and summer patch burning is being tried, too. Sedivec told me: “From the first year of burns, we had a 60 to 70 percent reduction in Kentucky bluegrass and a two-fold increase in forbs. With fire, you get a different plant community, but also get a very lush, high-quality plant community.” And, he says, the cows and calves grazing on the patch-burned areas gained more weight than a control group.

As farmers, ranchers and homeowners, we look for “natural” ways to control pests if possible – flea beetles to control leafy spurge, fungal spores to control grasshoppers, parasitic wasps to control corn rootworms and emerald ash borers. Fire is nature’s way of getting rid of stuff that the ecosystem is better off without. But prairies today are dotted with small towns, farmsteads and fences and all sorts of rural residences.

Most people think fire is not an acceptable choice. It’s too risky. People and their buildings, livestock and machinery have gotten in the way of nature’s remedy, so we look for other answers.

Al Gustin is a retired farm broadcaster, active rancher and a member of Mor-Gran-Sou Electric Cooperative.