Suck it up, buttercup.

For many years, generations even, that was a guiding “attitude” in the first responder community, Mona Thompson says.

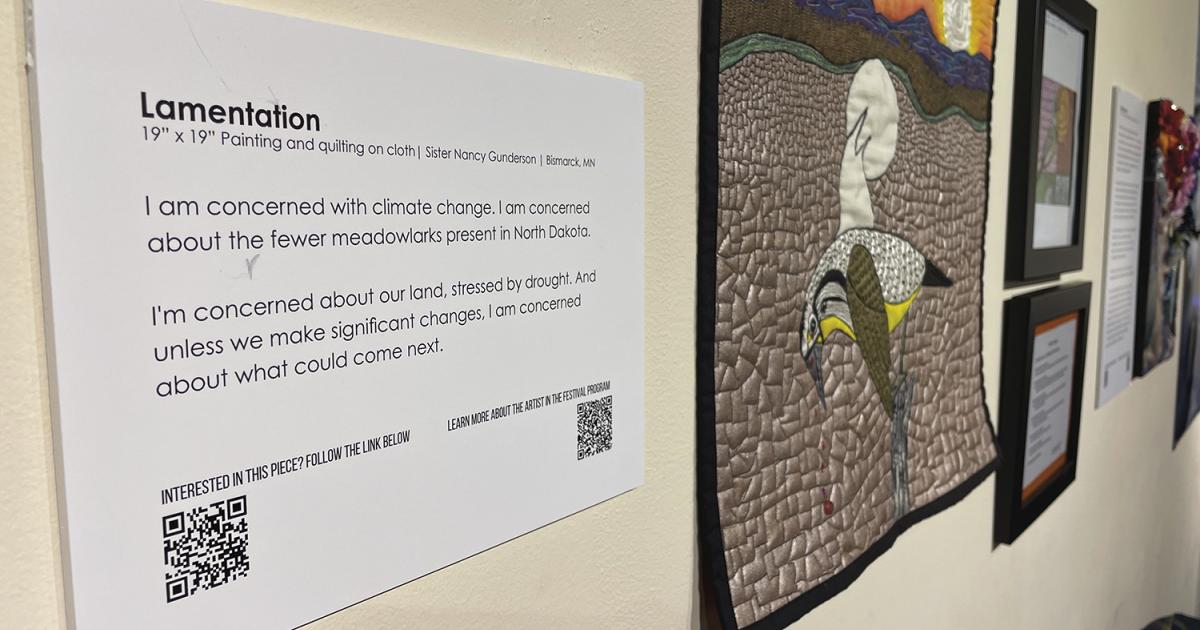

Mona Thompson, Kidder County Ambulance director and paramedic, has been working to improve mental health services for rural first responders, who face trauma and significant stress by the very nature of their jobs. Photos by NDAREC/John Kary

“There’s this culture of being tough and having to suck it up, and that is why you have such a high burnout rate,” she says.

She speaks from experience. In 1991, Thompson moved to Steele from Wisconsin. A new neighbor asked her if she wanted to join the ambulance squad. She agreed. The neighbor handed her a pager, and just like that, she was on call.

Four hours later, the pager went off.

“I had no training whatsoever, no orientation. I didn’t even know the crew. And I was just told to show up to the ambulance hall,” she recalls.

But after that first call, Thompson’s interest was piqued. She enrolled in emergency medical technician (EMT) classes in Bismarck, knowing she never again wanted to be in the position “to not know a thing.”

“I found out I loved doing this,” she says. And just three years after that first call, Thompson graduated from paramedic school and began a new role as co-director of Kidder County Ambulance.

Almost 30 years later, Thompson is still at the helm of the emergency medical services (EMS) system in Kidder County, the only paramedic left on the 62-person squad. On top of doing this work, Thompson has dedicated herself to another passion project in recent years, one she hopes to continue after retiring her scrubs and Tigger stethoscope.

Her focus? Changing the tide of the tough, suck-it-up attitude in EMS, creating mental health awareness and improving mental health services for first responders.

TRAUMA AND STRESS

“One of the biggest challenges for rural EMS is that the people we take care of are friends and family, they’re the people we know,” she says. “You develop close relationships throughout your entire community, and now, one of these people, that is a dear friend or loved one, is in a critical condition.”

The very nature of the job exposes EMS providers, and other first responders, to trauma. Those experiences can put individuals and organizations at risk for a range of negative consequences, including significant stress, Thompson says.

“We see things the average person should never see, and will never see, in their lifetime,” she says. “It’s not normal to see and experience the things that we do, but you try to live normal after something that was very abnormal.”

And eventually, as an EMS responder, you’ll get “that one call that is going to make you see the world differently.”

‘MY CALL WITH JARETT’

On a beautiful June day in 2014, Thompson got that call.

Three local teenagers had been in a car accident returning home from a daytime fishing trip. Thompson knew the boys well; they were her son’s friends and classmates.

“My call with Jarett – it was a bad call,” Thompson says.

Two of the teens were badly injured, but survived the accident and physically recovered. Jarett Wolf lost his life.

“Jarett was like my third son,” Thompson says. “It was a very traumatic call of someone who is like my own child, and the rest of the crew knew him, too. It was very traumatic for everyone.”

In the aftermath of such tragedy, Thompson did what she was trained to do – she took care of others. She lined up two critical-incident stress debriefings (CISD), which were introduced in the 1980s as a way to manage the psychological toll of the critical incidents first responders face. A debriefing team, of peer-EMS personnel, is brought in to review the incident with the responders on the call and talk through individual reactions to it.

It wasn’t until a few years later, when she was more removed from the trauma and the “tough year” that followed that Thompson grasped some new perspective.

“Someone should have been there to say, ‘You let us take care of you,’” she says. “We didn’t have someone there to care for us when we got back (from the call).”

Around this same time, a crew member who responded to the same call had told Thompson they couldn’t do EMS anymore. They shared their struggles and opened up about how the call had affected their mental health.

Thompson understood. She immediately went on a search for mental health services, including counseling, that went beyond the limited scope of CISDs. She hit roadblocks at every turn, at every level, including the state of North Dakota. She found one resource, a 24/7 disaster distress hotline for first responders experiencing emotional distress, operated by The Code Green Campaign.

“There were still no real counseling services for EMS, as mental health therapists generally practice in larger urban areas, and access to these services in rural communities are extremely limited,” Thompson says. “EMS providers are a unique breed of folks. They run into and manage situations the public runs from, and the repeated exposure to traumatic events can increase the likelihood of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) during their careers. Because of the unique situations they face, counseling services specific to EMS are needed, and there were none locally.”

And so, Thompson again did what she was trained to do – she took care of others – by taking action and raising her voice to the cause of improved mental health services for first responders.

BREAKING THE STIGMA

Since Thompson brought the issue of mental health services for EMS providers to the North Dakota Emergency Medical Services Association, she has worked hard to achieve progress. She’s testified in front of legislative committees, chairs the North Dakota Emergency Medical Services Association’s Mental Wellness Committee and developed a mental wellness course for EMS services across the state that was introduced last spring.

“The feedback (from the course) was phenomenal,” she says. “Finally, thank you. I didn’t feel like I could ever talk about this,” was a common response.

The stigma associated with mental illness, both in society and the EMS community, is a huge problem, Thompson says, and awareness is a key component to breaking down that barrier.

Thompson has eyes on helping to develop a professional mental wellness program that can be used by EMS systems across the country. One of her former responders, who she trained and partnered with on the ambulance squad, is now a professional mental health counselor with an interest in the same work. Thompson hopes to collaborate with her former partner on program development.

Funding is always an issue in rural EMS, and Thompson’s mental wellness effort is included in that. But she soldiers on.

“Baby steps,” she says. “I want to do this right.”

GONE FISHING

In a way, Thompson’s mental health work might be a sort of therapy in itself. It keeps her busy and her memory of Jarett close. And she would tell you she certainly sees the world differently now.

She strikes a balance between her work life and personal life, and prioritizes that over the beeping of the pager. It’s a stark contrast to the EMS culture she knew for most of her career, and it’s one she fosters amongst her Kidder County Ambulance crew.

“You have to have a life outside of EMS. Your family, the things you love in life, always put them first,” she says.

It’s a lesson the whole Thompson family has learned, in fact. Thompson met her husband, Stuart, through the local ambulance service, where he was an EMT. He is now a volunteer firefighter, along with their youngest son, Tommy, who is also an emergency medical responder (EMR). Their eldest son, James, is an EMT, and both sons volunteer with the ambulance service.

“I’ve seen so much, but it’s that connection you feel with your patient and your community. You need time. It’s OK to take a break from this. Looking back, I would have taken a few months off after Jarett’s call,” she says. “I know that time away from here is very important.”

As such, Thompson does what she was not trained to do – she takes care of herself, too.

“When I go fishing, I go fishing,” she says.

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.