On a beautiful evening in late August, we sat alongside the Bohemian Hall south of Mandan and listened as Chuck Suchy sang about the hall and this “place” where he grew up and still lives. As he sang, a semi-truck barreled past on Highway 6, after hauling a load of grain to market. I thought of all the changes the hall has seen.

The hall was built in the early 1900s, when the traffic would have included horse-drawn wagons and carriages. A half century later, there would have been pickup trucks carrying 80 bushels of wheat or two cows or a half dozen market hogs from many diversified farms. The cars driving by often had cream cans in their trunks.

Fast forward another 75 years and it’s semis hauling grain from larger, fewer farms to sub-terminal elevators. Cattle ride in semis or long trailers, headed to market, or sometimes to pastures many miles away. Tankers haul milk from the few dairies left to a plant in Minnesota. School buses carry children to and from consolidated schools.

A dozen years ago, I wrote, “This new agriculture, I think, is certainly more sustainable than my dad’s agriculture. From the standpoint of productivity, we’re leaving the land in better shape than we got it. But it’s obviously not more sustainable from the standpoint of maintaining rural schools, churches and communities.” After reading that, an agricultural researcher wrote me saying he now wonders if all the decades of agricultural research were too narrowly focused.

As we are about to turn the calendar to a new quarter-century, we wonder what rural North Dakota will look like. It gives us pause to read the average age of farmers continues to climb. One study suggests 70% of U.S. farmland will change hands in the next quarter century, or less. Who will buy all that land? Will it be absorbed by beginning farmers, existing producers or outside investors? Will more small towns wither and die?

Some find all this change regrettable. Others see it as progress, or simply inevitable. Regardless, the social fabric of rural North Dakota won’t be the same, nor will the traffic passing the Bohemian Hall.

___

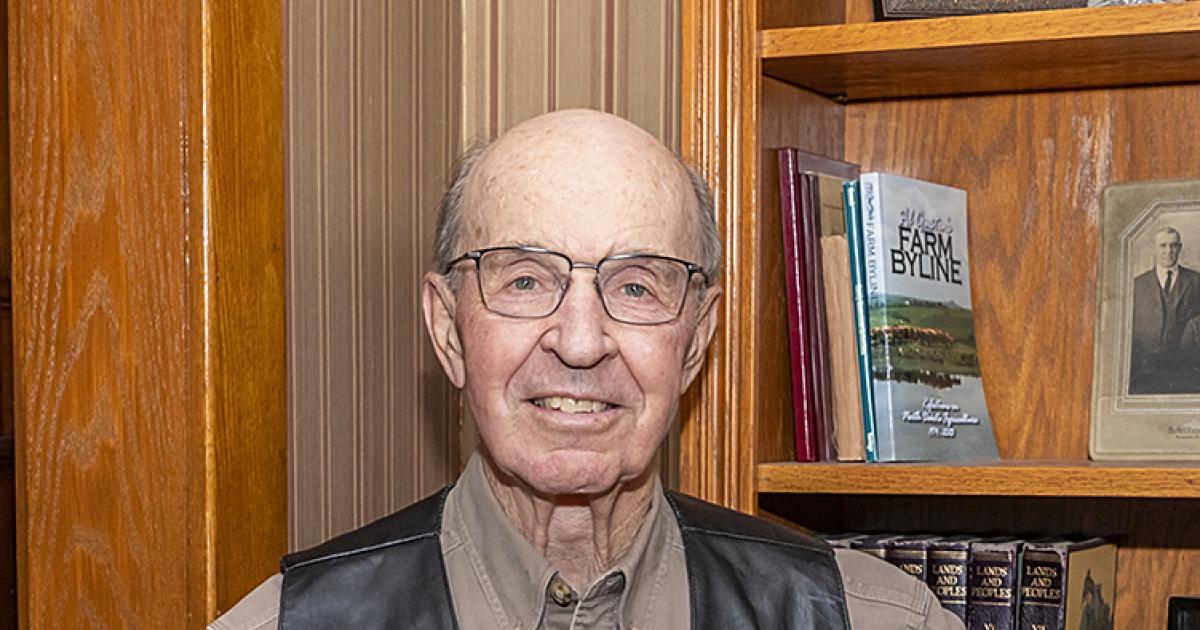

Al Gustin is a retired farm broadcaster, active rancher and a member of Mor-Gran-Sou Electric Cooperative.