It wouldn’t take but a few moments sitting with Robert “Bob” Hunter, Maddock’s oldest resident, to understand why Tom Brokaw coined the familiar term “the Greatest Generation.”

At 100 years old, Hunter still lives in the home he built decades ago, kitty-corner from the old Maddock Aggies school, now the high school. An American flag flies in his yard, near the parked car he still drives. Inside his home, the TV news hums in the background of his Solitaire game, which he does to “stay sharp.” A hallway bookshelf holds the Bible, Lutheran hymnals, Maddock history compilations and Webster’s New Students Dictionary. Adorning every possible space are pictures of his successful and well-educated family. He is dressed in what must be one of the proudest uniforms he’s ever worn – a shirt identifying him as a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) grandparent.

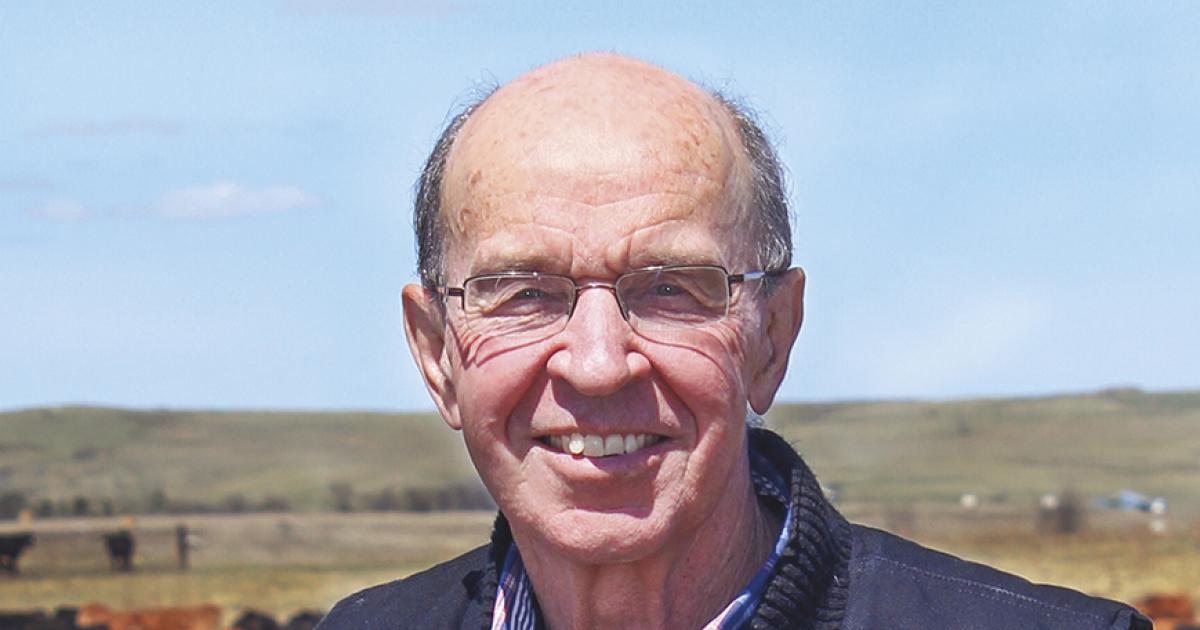

Robert “Bob” Hunter, Maddock’s oldest resident, holds his U.S. Army portrait, taken over 75 years ago during his World War II service. Photos by NDAREC/Liza Kessel

Set amongst Hunter’s photographs is a small black-and-white image of a handsome young man. His light eyes shine under a U.S. Army service cap. They are the same blue eyes looking at me now from behind a pair of glasses.

Hunter is one of 16 million Americans, and 60,000 North Dakotans, who served in the military during World War II.

The year 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of Victory in Europe (V-E) Day and the end of WWII. Each passing day, 245 WWII veterans are lost, based on U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) projections calculated before the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, Hunter is one of just an estimated 300,000 U.S. WWII veterans still living in 2020, according to the VA.

By the time we reach the 100th anniversary of WWII’s end, the Greatest Generation may be no more.

Hunter’s story is one of 16 million that became one of 300,000. His is no more or less important than the others. And if you ask him about his service, Hunter’s response will likely be the same as most other WWII veterans.

“It was just part of that time,” he says. “I wasn’t any hero. I just did it and served my time.”

STRAIGHT-EDGED RAZORS AND A FOXHOLE

Like 10 million other American men, Hunter was drafted into the military during WWII and boarded the “troop train.” After being sworn in at Fort Abraham Lincoln and processed at Fort Des Moines, Iowa, Hunter was sent to Fort Sill, Okla., for basic training, where he was to be trained in Army artillery.

“I’d been there a couple weeks, and I got a notice that I should report to regimental headquarters,” Hunter says. “Jeez, I was scared out of my witness.”

Upon arrival, Hunter saluted a brigadier general, who told him the results of his Army General Classification Test (AGCT), which is used to determine intelligence and other abilities of entering servicemen. Hunter’s high scores made him eligible for Army Officer Candidate School (OCS), where he would receive training to become a commissioned officer.

“I was just overwhelmed. I didn’t know my left foot from my right yet, so I turned ‘em down. I didn’t go, and as a result, I never got promoted all the time I was in the Army,” Hunter chuckles.

Eventually, another opportunity came up, one Hunter agreed to this time. A barber was needed on base. Hunter’s father, Roy, had a barbershop back home in Maddock, and Bob had joined the family business after graduating from barber school in Fargo at the age of 17.

Bob joined a “fantastic barber and Italian from New York,” Tony Capazilli, in the regimental barbershop, offering 50-cent haircuts and shaves with straight-edged razors. A few years later after barbering on bases in Oklahoma and Texas, Bob got notice that he was being transferred to an Army base on the East Coast to be trained as an infantryman.

While there, Army doctors performed an operation on Bob for a foot bone issue, leaving him unable to continue infantry training. He was then transferred to Fort Lee, Va., and the non-combat U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps, a logistics branch of the Army.

Nearing the end of the war, Bob was to report to Fort Lewis, Wash., where he would be shipped overseas into the Pacific Theater. The cross-country trip allowed Bob a weeklong furlough, where he enjoyed time with his wife, Marie (Liudahl) Hunter, and eldest child in Maddock.

In 1944, Bob arrived on a “little island” off the coast of Okinawa, Japan, Ie Shima, “where (WWII correspondent Ernie) Pyle was killed.” It was there, for Bob, history repeated itself.

“They found out I was the only barber on the island,” he says.

And so, Bob set up shop in an Army tent, giving haircuts and shaves with a straight-edged razor once again. He would continue to welcome servicemen to his barber chair on Ie Shima until the end of the war.

The most memorable part of his military service?

“When I heard the war was over,” Bob says. “They started celebrating on this island, and these anti-aircraft guns, they were shooting straight up in the air, you know, to celebrate, and the shrapnel was coming down. I hit a foxhole – the only time I was (in a foxhole) in the service – and I stayed there for two-and-a-half hours that night before they calmed down!”

Being in that foxhole was a moment of absolute pure joy, Bob says. He was going home.

HOMECOMING

Bob returned home to North Dakota following his discharge at Fort Lewis. When he deboarded the Northern Pacific rail in New Rockford, Marie was waiting for him.

The Hunters returned to Maddock in 1946 and raised three children – son, David, and daughters, Judy and Linda. Bob rejoined the family business, which also included a restaurant for a time, in Maddock, and retired from barbering in 1985.

“The most I ever got (for a haircut) was $6,” Bob says. “Last time I got my hair cut, it was $17.”

His family is a source of great pride, and he considers “raising a family” to be one of his crowning achievements. Sadly, Bob lost his wife to cancer in 1999. Last year, two of his children, Judy and David, also passed away.

Despite those hardships, Bob keeps himself busy. He is known in the Maddock community as a skilled gardener and isn’t showing signs of slowing yet.

Randy Simon, a Maddock resident and Northern Plains Electric Cooperative board member, recalls driving through town a few years back and seeing Bob on a stepladder, cleaning out his gutters!

While the centenarian admits to having a sweet tooth and drinks a gallon of milk each week, he doesn’t quite know the reason behind his longevity. He does offer, though, one bit of advice.

“Don’t smoke,” he says.

Bob has remained connected to a community of veterans since the end of WWII as a member of The American Legion, participating in the local honor guard and many military ceremonies over the years. Earlier this year, he was recognized for being a 75-year member of The American Legion. There are just 37 North Dakota veterans who have the distinction of being members of The American Legion for 75 years or more.

And, Bob was the first Maddock veteran to donate his military uniform for display in the Maddock Community Museum. The only piece of his uniform missing from the local museum is Bob’s combat boots. His son wanted those, says museum curator Jimmy Gilbertson, so he made a $100 donation to the museum and walked out with Dad’s WWII boots.

CONSIDERATIONS OF HEROISM

Combat scenes are classically used in popular culture to depict war. But the stories of war, and those of our veterans, are far more diverse than that. No movie, book or magazine article can truly capture the full picture of war or that of a veteran’s military service.

Bob doesn’t consider himself a hero. But consider, for a moment, how many men, experiencing a trauma few could understand, sat in Bob’s barber chair over the course of the war. Consider how many conversations Bob had with his comrades, perhaps listening to whatever it was they needed to talk about, or giving them a brief reprieve from the realities of war, or providing a temporary taste of normalcy, like getting a shave and a haircut from the local barber in hometown U.S.A.

There were many WWII veterans like Bob, who served in capacities that maybe weren’t top-of-mind, but undoubtedly necessary to the war effort. It was the contributions of many that brought an end to WWII 75 years ago.

In a story published on the U.S. Department of Defense’s website, 10 odd jobs of WWII were highlighted and include: blacksmith, meat cutter, horsebreaker, artist and animation artist, crystal grinder, cooper, model maker, pigeoneer, field artillery sound recorder and airplane woodworker.

Add “barber” to that list.

Cally Peterson is editor of North Dakota Living. She can be reached at cpeterson@ndarec.com.